Strategic (Knowledge)Management

Here, a new approach to strategic (knowledge) management will be presented.

The use of brackets is intentional, since “knowledge management” is a tautology — at least according to Peter Drucker’s definition:

»Management is the application of knowledge to knowledge« — Peter F. Drucker

Thus, in the following, we will concentrate on knowledge — or rather on a qualitative variety of it, which is of enormous significance to strategic management and the creation of organizations.

»Scientia et potentia humana in idem coincidunt« — Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon’s famous quotation became a dictum in its English translation: “knowledge is power.” Indeed, positions of knowledge determine the capacity to act and thus the potential for success — both of and within organizations.

Neuberger distinguishes between three “faces of power” with regard to the distribution of knowledge.

- The first is characterized by open confrontation: opposing parties pursue conflicting objectives, so that either the stronger one wins or a compromise must be found.

- In the second, one party can, from the very beginning, restrict the number of alternatives to those it desires, giving the other side at least the illusion of freedom of choice, despite objective disinformation.

- In the third, neither opponent can see any alternative: instead of controlling their knowledge, they are virtually controlled by it.

This situation corresponds to Passive (or Qualitative) Disinformation. I refer to the corresponding units of knowledge as (qualitative) blind spots, after the biological phenomenon. Their effect can be illustrated by the following experiment:

Shut your left eye, focus on the cross in the picture with your right eye, and gradually alter the distance between you and the image.

As soon as you reach the correct distance, the square will disappear. Every human being has a visual blind spot at the junction between the optic nerve and the retina. This partial blindness is always there, even if it usually goes unnoticed. You don’t see that you can’t see!

Although this experiment was restricted to visual perception, similar phenomena also exist in other areas, in which information or knowledge is processed. I refer to the corresponding units of knowledge as (qualitative) blind spots, after the biological phenomenon.

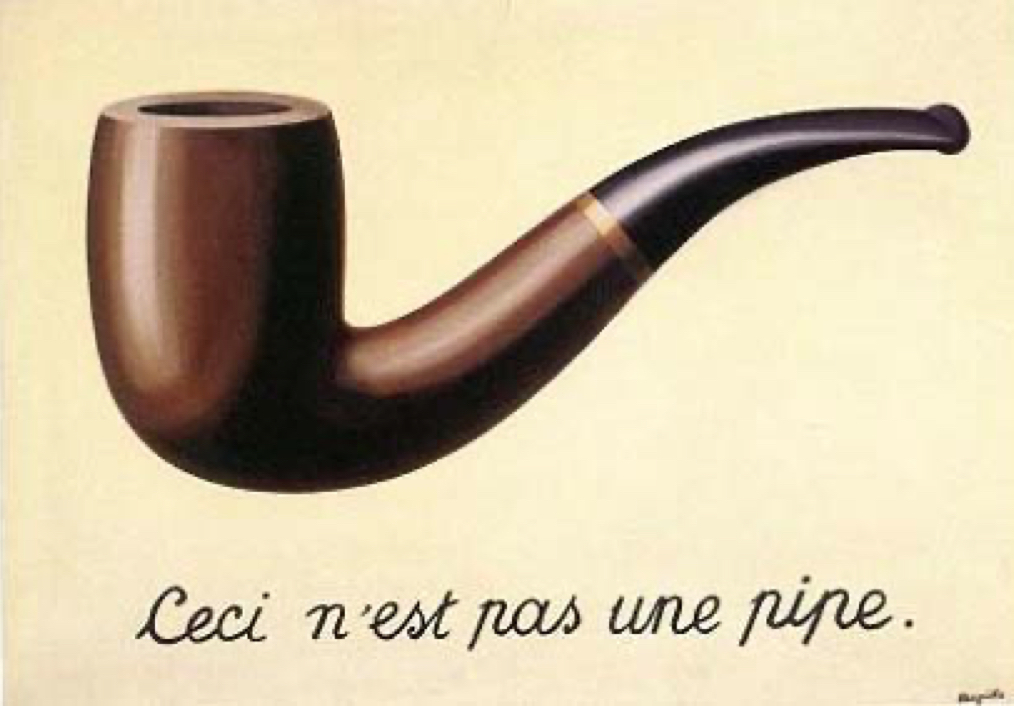

Qualitative blind spots exist in any knowledge base whenever a model is not recognized as a model. Models are representations of something they need not necessarily resemble. Take, for example, abstract art — or language itself.

In 1641, the German linguist Schottel even went so far as to praise the affinity of things to their (German) designations — although it can hardly be denied that the figure 5 has nothing “five-ish” about it, and that the word table is not especially table-shaped.

Even in the following prime example of reification, a poem by Eugen Roth, “sheep” is nothing but a word:

One man calls another “sheep,”

Whose wounded pride runs far too deep.

“Alack!” he cries, “I won’t take that!

Retract your word — apologize, prat!”

“No,” says the first, “why should I care?”

The sheep stands lost, with vacant stare.

And thus it goes, as all may see —

The sheep, my friend, is you and me.

Models are not identical with their originals. A perfect copy would cease to be a model — it would be the original itself. This problem is best illustrated through mapping paradoxes:

Imagine part of England were completely flattened and a cartographer drew a map of England on this plain — a map perfect down to the tiniest detail. Then on this map there would have to be a map of the map, and on that one a map of the map of the map… and so on, to infinity.

Even if we think only in terms of measurements, an image on a “realistic” scale of 1:1 is impossible, as chaos research has shown in the famous example of the British coastline.

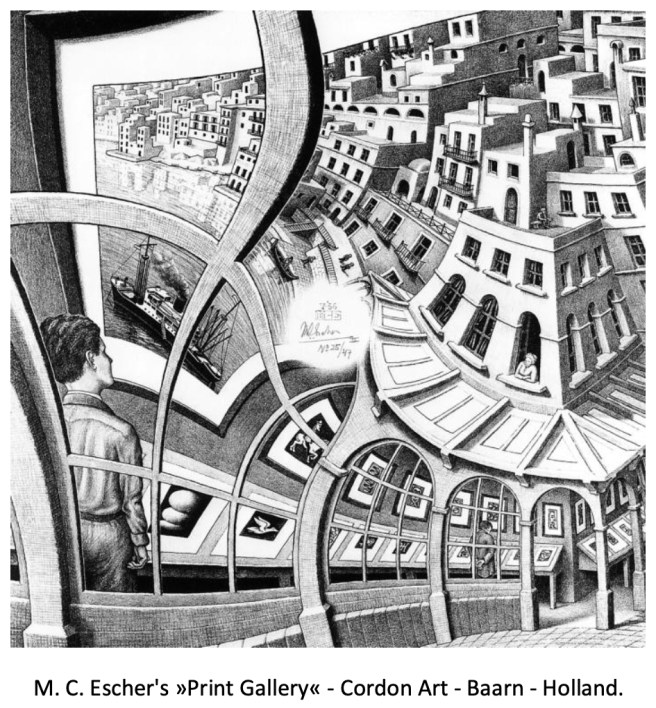

The common denominator of all blind spots may be that one is, so to speak, trapped by one’s own model. This is expressed particularly clearly in Escher’s Picture Gallery:

»A picture held us captive. We were not able to escape, for it was in our language, which seemed only to repeat it relentlessly« —Wittgenstein

At the bottom right, we see the entrance to an art gallery. A young man is looking at one of the exhibited pictures, which shows a ship and a few houses near the harbour. On the right, the row of houses continues.

If we look at the bottom right-hand corner, we can see a house with the entrance to our art gallery — so the young man is captured in the picture he is looking at.

The consequences are remarkable: Man — a “non-trivial automaton” per se — is being trivialized by Passive Disinformation. His blind trust in the reality of a model causes him to lose sight of alternatives and to become more predictable.

Typically, this endogenous restriction conceals from the individual his own exogenous restriction. As former German Chancellor Adenauer put it: We all live under the same sky, but not all of us have the same horizon.

The set of all an individual’s models defines their horizon. If something is missing, the individual does not even know what they do not know. If they had a clue, they could search for it; otherwise, they can only stumble upon it by chance.

It is the incongruence of our horizons that causes all verbal and non-verbal communication breakdowns. Only mathematical terms ensure clear and unambiguous communication.

Kant even maintained that “natural science is only science to the degree to which mathematics can be applied to it.”

It is indeed possible to adapt or transfer mathematical models (that is, numbers) without loss — think of digitized music, images, or films, which can be copied without the slightest degradation in quality.

But that should not blind us to the fact that a loss of information has already occurred at the point of model creation — and that this loss recurs with every retranslation.

Einstein accordingly observed that mathematical theorems are not reliable insofar as they refer to reality; they are reliable only insofar as they do not refer to reality. So much for the soft core of hard facts.

In fact, no definition — unless purely mathematical — can be anything other than a classification.

That is why defective communication is not the exception but the rule. Yet it remains unrecognized when practiced within the shared set of blind spots — a kind of “standard interface.”

On the one hand it guarantees organizational continuance, but on the other it restricts the capacity to act.

According to Ashby’s Law, this is unproblematic as long as the complexity of the environment changes more slowly than the system’s adaptability and its ability to change the environment — which may be taken as its intelligence.

Passive Disinformation, as a qualitative limitation, is therefore of particular relevance to management. My fractal management approach provides a solid and system-conform basis for the organization of organization.

Knowledge Quality

Wherever ghosts may be appearing,

The sage finds welcome and a hearing;

And that his art and favour may elate,

A dozen new ghosts he’ll at once create.

You’ll not gain sense, except you err and stray!

You’ll come to birth? Do it in your own way!

— J. W. v. Goethe

What is knowledge, and how can its quality be measured or influenced?

These questions can scarcely be answered sensibly without considering the role of ignorance.

The fundamental difficulty in dealing with knowledge lies in the fact that the very instruments we employ are themselves forms of knowledge. Hence, knowledge defines itself. Progress in understanding it remains confined within a narrow frame: apart from the proliferation of categories, we encounter circular definitions (vicious circles), as discussed by Plato in his Theaetetus, and even paradoxes.

This basic problem can easily be illustrated by the following image:

A hand sketches a hand which sketches this hand, and so forth…

A similar situation arises when you say, “I am lying.” Are you lying at that moment, or are you telling the truth? The classical formulation of this problem is the Liar Paradox, attributed to the Cretan Epimenides, who claimed that all Cretans lie.1

According to Wittgenstein,2 however, the problem can be approached from two sides: in order to define knowledge, it is necessary to know both sides of the definition — in other words, one must know what one cannot know.

My fractal-based view3 therefore illuminates this side of the definition from a pragmatic and knowledge-economical perspective.4 It focuses particularly on aspects of disinformation, with emphasis on the phenomenon of passive (or qualitative) disinformation.

Disinformation and the Management of Knowledge Quality

The intelligence and success of an organization5 depend on its aptitude for purposeful change.

Obstacles to organizational improvement6 can arise from either reluctance or inability. While inability can often be remedied by increasing knowledge,7 unwillingness is more difficult to address8 and can even affect the simplest forms of knowledge transfer.

Thus, decision makers often find it difficult to determine whether they are confronted with relevant or useless information: if one does not know something, one cannot even know what one does not know.

On the other hand, Arrow’s Paradox typically applies to the provider of information, who must judge the value of that information — a value that depends greatly on context. Therefore, such knowledge must be transferred. Since this transfer may be free for the recipient, the willingness to provide it is accordingly reduced.

This fundamental problem does not disappear simply by being ignored. Closing one’s eyes to these difficulties can lead, at best, to trivialization9 or to the establishment of new forms of lip service10 — accompanied by further losses in effectiveness. This increases the organization’s complexity, but not its competence in solving problems.

However, obstacles to improvement are not necessarily (micro-)politically motivated; they are often caused by qualitative disinformation.11 This phenomenon is not confined to specific contexts but can occur in all areas.

My fractal management approach provides an effective basis for addressing this problem. Fractal analysis can overcome the tension between self-reference12 and Kirsch’s haircutter13 and can be applied as a scale-invariant, generative best practice.

A fractal-based perspective offers an efficient starting point for qualitative corporate and organizational governance. The integrative approach encompasses the areas of personnel, organization, and strategy.14

Innovation

Those who are slow to know suppose

That slowness is the essence of knowledge.

— Friedrich Nietzsche

Learning can leave you more stupid, and in many cases such deterioration is even desired: organizations are (knowledge-)ecological systems that display various kinds of pathologies. One person’s gain can be another’s loss – while some losses, conversely, are reciprocal.

Organizational pathologies usually persist despite better knowledge; only very few such problems arise by mere chance. One of the simplest approaches to solutions consists in reinterpreting the problems themselves – Luhmann calls this modern exorcism: “The [consultant …] advises […]: Your problem is severe; keep it. It is important to you; it is essential and dear to you – to such an extent that you even agree to pay the one who tells you this.”15 Thus, needs become virtues.

Other attempts at solution, however, shift the focus by creating entirely new centers of problem – after all, suppression can also be interpreted as a kind of solution.16

Organizations are based on knowledge and are subject to a central regularity: the incomplete knowledge of their members on the one hand, and the asymmetries of knowledge between them on the other.17 Moreover, any knowledge already available may itself be defective – and consequently, so may the organizational structures built upon it. Those who are looking for sustained solutions here have to face the basic problem of the quality of knowledge.18

Apart from this highly difficult question, such basic research also carries the danger of treading on “forbidden” ground. As a Chinese saying puts it: one must swim against the current to reach the spring,19 – to say nothing of the ever-present resistance to change.20

A sustained, effective solution requires that the basic problem be de-tabooed. Dealing with it does not necessarily lead to conflict. Here, knowledge-fractal analysis offers a culturally, politically, and ideologically neutral – as well as adaptive – procedure. Beyond providing new pragmatic approaches for the management context, it also offers the opportunity to evaluate21 and shape situational determinants.

The quality of knowledge – and thus of organizations themselves – becomes pragmatically measurable and therefore purposefully improvable through the discovery of the phenomenon of Passive (or Qualitative) Disinformation.

This opens up new approaches toward a more intelligent and more successful organization of organizations.

Culture & Competence

No problem can be solved from the same consciousness that created it. — Albert Einstein22

The culture of a social system is largely characterized by the totality of its effective goals. This applies not only to artistic creation but can extend from everyday life to highly specific problem areas.23

Evaluations express the degree to which goals have been achieved, and they are culture-dependent. What is valued positively tends to be reinforced; what is evaluated negatively is suppressed; and what is not evaluated at all is, as a rule, ignored.

The goal system of an organization influences which problems are perceived and which possible solutions are even considered. Such consideration is, by its very nature, error-prone.

Not everything that is effective is good; and not everything that is good is effective. In problem analysis, perception may be wrong — or the wrong things may be perceived.24

Nietzsche even goes so far as to characterize successful results as rare, accidental events:

“And when once truth did achieve victory, ask yourselves with good mistrust: What powerful error fought on her side?”25

The error may be enormous, yet it is rare for an observer to draw the right conclusions from discrepancies between perceived and conceived reality:

And he concludes:

“A dream it was — the whole event!

For,” he reasons, confident,

“What must not be, cannot be — hence it went.”26

Cultures themselves can therefore be flawed—even pathological—and organizational research on this subject fills volumes.27

On closer examination, most of the relevant problem areas can be traced back to aspects of disinformation. Different cultures display varying degrees and qualities of disinformation. The principle holds: the more disinformation-intensive an organization is, the lower its ability to respond to changing environmental conditions — a capacity that can also be interpreted as its intelligence or problem-solving competence.

The real challenge, therefore, lies less in implementing time-bound, fashion-driven recipes for success28 than in designing organizations that are robust against disinformation.

Interestingly, even the most problem-solving-incompetent culture possesses competence concepts and corresponding “methods” that are fully compatible with its own dysfunction. An American proverb parodies this fact:

Those who can, do.

Those who can’t, teach.

Those who can’t teach, teach teachers.

Not everywhere that “competence” is written on the label does competence actually reside inside. In this context, institutionalized competence development often leads in practice to the emergence of core incompetencies: a qualification in ineffectiveness.

Indeed, without taking aspects of Knowledge Quality into account, there is no alternative to the development of pseudo-competencies. The “implicit non-knowledge” of passive disinformation typically serves as a goal in itself for those affected, representing nothing less than solidified incompetence — even if it may, in certain cases, be interpreted as a qualification.

Effective, disinformation-robust organizational design requires breaking The Ultimate Taboo. Genuine cultural improvement cannot be achieved by “more of the same,” but only by breaking “the same.”

A focus on knowledge quality enables effective, dynamic competence development in balance with cultural interests.

Thought-Parasites

The most fundamental of all questions does not concern where we come from or where we are going. The most basic — and at the same time most difficult — of all questions is this: What is knowledge? Consider this, how reliable is the content of an answer if we cannot judge the reliability of the answer itself?

The problem in answering this question lies in the fact that the instruments we apply are themselves composed of knowledge. Progress in understanding has therefore been constrained within narrow boundaries.

Instead, continually new thought-parasites are created, as expressed in this slightly modified verse:

One should know that thoughts have fleas

Upon their backs to bite ’em;

And the fleas themselves have fleas,

And so ad infinitum.

Our basic problem cannot be answered sensibly without consideration of disinformation. According to Wittgenstein, in order to define the limits of knowledge, it is necessary to know both sides of the definition—in other words: one should know what one cannot know.

The phenomenon of Passive Disinformation (the Qualitative Blind Spot) is the key to Knowledge Quality. Before its recognition, there are hardly any alternatives to blind identification. Any reasoning that has contradicted the traditional approach has, until now, been demonized:

Nature is sin, and mind is devil,

They nurture doubt, in doubt they revel,

Their hybrid, monstrous progeny.

— Goethe

Or at least criminalized:

Behold the believers of all beliefs! Whom do they hate most? The man who breaks up their tables of values, the breaker, the law-breaker — yet he is the creator.

— Nietzsche

Servan wrote in 1767: “A stupid despot may constrain his slaves with iron chains; but a true politician binds them even more strongly by the chain of their own ideas; […] this link is all the stronger in that we do not know of what it is made and we believe it to be our own work; despair and time eat away the bonds of iron and steel, but they are powerless against the habitual union of ideas — they can only tighten it still more; and on the soft fibers of the brain is founded the unshakable base of the soundest of Empires” (quoted by Foucault).

The development of our globally networked knowledge society represents a leap in cultural evolution that can scarcely be mastered with the largely unchanged control mechanisms of previous centuries — especially for nations poor in natural resources. Even the soundest of Empires can sink to the level of developing countries if poor decisions are made or basic conditions change.

Now, however, many organizations are founded on disinformation — and kept alive more or less artificially. The introduction of sound information can, in such cases, lead to collapse.

On the other hand, making this topic taboo creates new problems and exploitable gaps — not to mention the ethical dimensions involved. What is required is a responsible approach to our basic weakness.

Effect & Effectiveness

In the beginning was the Deed!29

— Goethe

Limitations of effectiveness may be intentional30 or may arise involuntarily from the repeated application of simple rules. In this way, complex systems emerge that hinder their own success and efficacy.

For every persistent impediment, there usually exist customized justifications—or at least explanations that appear plausible. It is common to observe that pathological systems provide their own legitimacy.31

Thus, it is hardly surprising that a “fall from the tenth floor down to the ground floor proceeds entirely without problems”.

Disinformation is the most effective of all barriers to effectiveness—and even here, professions of usefulness are never far away.32 Alongside missing and false information, misvaluation counts among its simplest manifestations: irrelevant or false goals are used as a basis. It is easy to see that with a flawed perception of the problem, one can hardly arrive at suitable solutions.33

Whether disinformation is actually harmful in a given context depends on the interests of the parties involved. After all, considerable profits can be generated from misguided value systems—even to the point of creating entire economies of ineffectiveness.

Furthermore, pseudo-solutions encounter far less resistance than perceptible change. As a result, ever new variants of avoidance solutions are encouraged (which also explains the inflationary trends of the consulting fashion industry), ranging from mere ineffectiveness to massive collateral and consequential damage.

Without taking the quality of knowledge into account as the actual core problem of the organization, rationalization concepts—apart from very hard, existentially threatening measures—can at best treat symptoms.

Rationality itself must become the starting point of a rationalization that neither inflates further, nor renders systems even less effective, nor merely ends in the loss of resources.

The proper response to dynamics and complexity is not simplification to the point of stupidity,34 but intelligent organization.

Rationality & Rationalization

The better is the enemy of the good.

Panta rhei — everything flows. Change is the rule in all real-world systems. One can influence it, or be influenced by it. It can create value—or destroy it.

Change, in general, can be viewed as innovation: the altered state is “new,” at least from the standpoint of the original condition. Yet not every innovation is also original.

The originality of innovations can be illustrated through a tree metaphor, for example in science (arbor scientiae):

The roots (radix, Latin) represent the foundations from which the trunk, branches, and leaves develop. Basic research, therefore, moves in the direction of the roots; it is radical (or original, if new roots are set).

The opposite direction builds upon existing structures and derives from them—it is derivative.

Depending on their impact, innovations can be classified as taxonomic or empirical. A taxonomy is a conceptual system that may refer to real phenomena outside of itself—but does not have to:

A man, as child, is taught to see

The world as adults claim it be:

That storks bring babies from the sky,

That Christ Child gifts at Christmas lie,

That Easter bunnies lay their eggs —

And faith in such still rarely flags.

For soon he sees, with some dismay,

That all were tales for nursery play;

But other lies, less pure, less mild,

He still believes—though not a child.

— Eugen Roth

Purely taxonomic innovations tend to solve problems one would not have had without the innovation:

Empirical innovations, on the other hand, have an effect whether or not one knows of them or believes in them.

Ideal-typically,35 innovation may consist of:

1. Old wine in new bottles,

2. New wine in old bottles, or

3. New wine in new bottles.

The first case makes the smallest demands on the innovator and is therefore by far the most common (cf. Karl Valentin: “Everything has already been said—just not by everyone.”)

Moreover, this form of change is easiest for its recipients to understand: it washes the fur, but does not get it very wet.

The second and third cases are rarer: whoever creates something genuinely new will usually underline this with new terminology.36 Yet “old bottles” can foster acceptance—innovation can thus disguise itself as a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

The third case places the highest demands on the understanding of those affected: to understand something, one must have understood it. Truly new things cannot be familiar and must initially overwhelm—yet this is precisely the starting point of all genuine learning.37

As long as the First Law of Thermodynamics applies, there will be no effortless change:

“Behold, good folk, here sits the man, in whom all arts be poured as one.”38

Change can bring much that is new and good—but the new is not necessarily good, and the good not necessarily new.

Innovation, ultimately, lies in the eye of the beholder: what is new for one person need not be new for another. The evaluation—and appreciation—of change also depends on the observer’s standpoint, and that standpoint is usually neither complete nor free of error.

Value creation can be understood as positively assessed change.39 Asymmetries in valuation, in particular, are a fundamental precondition for value creation and for the emergence of markets: cooperation and exchange generally presuppose that one’s own contribution is valued less than the expected return.

Before participating in an interaction, one must know that an exchange is even possible: what one does not know “does not exist” (and may only be discovered by accident). Alternatives that are unknown are very unlikely to be chosen.

In principle, the rule holds: the better informed you are, the greater your prospects for value creation; the worse informed, the higher the likelihood of value destruction. In real life, information asymmetries systematically disadvantage the less informed—otherwise, insider trading regulations, antitrust law, or state gambling monopolies would not exist.40

“Bubble economies” are a direct consequence of informational and valuational asymmetries. It is by no means confined to financial markets: bubbles begin in the mind and continue through organizations—up to entire economic systems.41

Organizational bubbles can, for example, be characterized by losses in effectiveness due to the pursuit of self-serving purposes—often without the organization’s awareness. C. N. Parkinson observed that cynics are generally wrong when they claim that the members of bloated bureaucracies are lazy or inactive. His studies revealed the unsettling fact that, as such organizations expand, their members usually work harder—to serve self-referential internal markets and thus contribute to further irrationalization.

Due to missing or faulty information, it is by no means rare for all parties involved in an exchange relationship to end up losing. Lose-lose situations occur more often than you might think.

Disinformation is the rule, not the exception. It resembles a renewable resource and demonstrates remarkable persistence as a stabilizing factor in ineffective organizations—particularly in its qualitative form.

Qualitative (i.e. Passive) Disinformation is the core problem of intelligent organizational design. It represents the central rationality barrier of the organization, even when it may appear “system-rational.”

Qualitative Disinformation requires adequate qualitative rationalization—rather than further deterioration through pseudo-solutions or optimization by over-expansion and irrationalization.

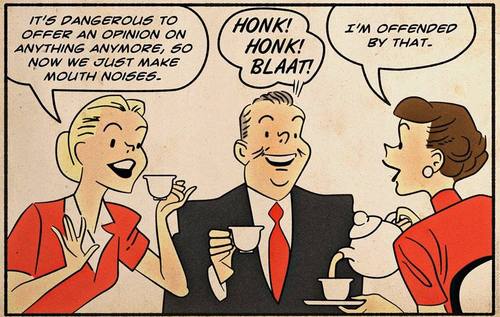

More than one creator of “management tools” has revealed the soul of a surrealist—though lacking the necessary self-irony:

There is a clear difference between claiming an effective solution for complex problems and actually handling them effectively.

Only the breaking of The Ultimate Taboo reveals a multitude of truly effective measures for sustainably dissolving the emergent, system-rational crusts that stem from the organizational core problem of qualitative disinformation.

Only solving this fundamental problem enables genuine rationalization.

The Entrepreneurial Craft

The most important factor of production in the entrepreneur’s craft is information — or, more precisely, knowledge.

His means of production are as knowledge-based as his most important products: his decisions.

Improving the productivity and quality of this kind of work is — without the right approach — far more difficult than in the case of manual labor.

Significant progress in that field was achieved above all through Frederick Winslow Taylor’s new approach. Peter F. Drucker provides both a profound overview and outlook:

“The most important, and indeed the truly unique, contribution of management in the 20th century was the fifty-fold increase in the productivity of the MANUAL WORKER in manufacturing. The most important contribution management needs to make in the 21st century is similarly to increase the productivity of KNOWLEDGE WORK and the KNOWLEDGE WORKER.

The most valuable assets of a 20th-century company were its production equipment. The most valuable asset of a 21st-century institution, whether business or nonbusiness, will be its knowledge workers and their productivity. […]

Within a decade after Taylor first looked at work and studied it, the productivity of the manual worker began its unprecedented rise. Since then it […] had risen fifty-fold […]. On this achievement rests all the economic and social gains of the 20th century. The productivity of the manual worker has created what we now call “developed” economies. […]

Taylor’s principles sound deceptively simple. The first step in making the manual worker productive is to look at the task and to analyze its constituent motions. […] The next step is to record each motion, the physical effort it takes and the time it takes. Then motions that are not needed can be eliminated—and whenever we have looked at manual work we found that a great many of the traditionally most hallowed procedures turn out to be waste and do not add anything. […]

Finally the tools needed to do the motions are being redesigned. And whenever we have looked at any job—no matter for how many thousands of years it has been performed — we have found that the traditional tools are totally wrong for the task. This was the case, for instance, with the shovel used to carry sand in a foundry — the first task Taylor studied. It was the wrong shape, it was the wrong size and it had the wrong handle. But we found it to be equally true of the surgeon’s traditional tools.

Taylor’s principles sound obvious—effective methods always do. But it took Taylor twenty years of experimentation to work them out. Over these last hundred years there have been countless further changes, revisions and refinements. The name by which the methodology goes has changed too over the century. Taylor himself first called his method “Task Analysis” or “Task Management.” Twenty years later it was rechristened “Scientific Management.” Another twenty years later, after the First World War, it came to be known as “Industrial Engineering” in the United States, the United Kingdom and Japan, and as “Rationalization” in Germany.

[… What] made Taylor and his method so powerful has also made them unpopular. What Taylor saw when he actually looked at work violated everything poets and philosophers had said about work from Hesiod and Virgil to Karl Marx. […] Taylor’s definition of work as a series of operations also largely explains his rejection by the people who themselves do not do any manual work: the descendants of the poets and philosophers of old, the Literati and Intellectuals. Taylor destroyed the romance of work. […]

And yet every method during these last hundred years that has had the slightest success in raising the productivity of manual workers — and with it their real wages—has been based on Taylor’s principles, no matter how loudly its protagonists proclaimed their differences with Taylor. This is true of “work enlargement,” “work enrichment” and “job rotation”—all of which use Taylor’s methods to lessen the worker’s fatigue and thereby to increase the worker’s productivity. It is true of such extensions of Taylor’s principles of task analysis and industrial engineering to the entire manual work process as Henry Ford’s assembly line (developed after 1914, when Taylor himself was already sick, old and retired). It is just as true of the Japanese “Quality Circle,” of “Continuous Improvement” (“Kaizen”), and of “Just-In-Time Delivery.” The best example, however, is W. Edwards Deming’s (1900–1993) “Total Quality Management.” What Deming did—and what makes Total Quality Management effective—is to analyze and organize the job exactly the way Taylor did. But then he added, around 1940, Quality Control based on a statistical theory that was only developed ten years after Taylor’s death. Finally, in the 1970s, Deming substituted closed-circuit television and computer simulation for Taylor’s stopwatch and motion photos. But Deming’s Quality Control Analysts are the spitting image of Taylor’s Efficiency Engineers and function the same way. Whatever his limitations and shortcomings — and he had many — no other American, not even Henry Ford (1863–1947), has had anything like Taylor’s impact. “Scientific Management” (and its successor, “Industrial Engineering”) is the one American philosophy that has swept the world — more so even than the Constitution and the Federalist Papers. In the last century there has been only one worldwide philosophy that could compete with Taylor’s: Marxism. And in the end, Taylor has triumphed over Marx.

In the First World War Scientific Management swept through the United States—together with Ford’s Taylor-based assembly line. In the twenties Scientific Management swept through Western Europe and began to be adopted in Japan. In World War II both the German achievement and the American achievement were squarely based on applying Taylor’s principles to Training. The German General Staff after having lost the First World War, applied “Rationalization,” that is, Taylor’s Scientific Management, to the job of the soldier and to military training. This enabled Hitler to create a superb fighting machine in the six short years between his coming to power and 1939. In the United States, the same principles were applied to the training of an industrial workforce, first tentatively in the First World War, and then, with full power, in WW II. This enabled the Americans to outproduce the Germans, even though a larger proportion of the U.S. than of the German male population was in uniform and thus not in industrial production. And then training-based Scientific Management gave the U.S. civilian workforce more than twice—if not three times—the productivity of the workers in Hitler’s Germany and in Hitler-dominated Europe. Scientific Management thus gave the United States the capacity to outnumber both Germans and Japanese on the battlefield and yet to outproduce both by several orders of magnitude.

Economic development outside the Western world since 1950 has largely been based on copying what the United States did in World War II, that is, on applying Scientific Management to making the manual worker productive. All earlier economic development had been based on technological innovation — first in France in the 18th century, then in Great Britain from 1760 until 1850 and finally in the new economic Great Powers, Germany and the United States, in the second half of the 19th century. The non-Western countries that developed after the Second World War, beginning with Japan, eschewed technological innovation. Instead, they imported the training that the United States had developed during the Second World War based on Taylor’s principles, and used it to make highly productive, almost overnight, a still largely unskilled and preindustrial workforce. (In Japan, for instance, almost two-thirds of the working population were still, in 1950, living on the land and unskilled in any work except cultivating rice.) But, while highly productive, this new workforce was still—for a decade or more—paid preindustrial wages so that these countries — first Japan, then Korea, then Taiwan and Singapore — could produce the same manufactured products as the developed countries, but at a fraction of their labor costs. […]

Taylor’s approach was designed for manual work in manufacturing, and at first applied only to it. But even within these traditional limitations, it still has enormous scope. It is still going to be the organizing principle in countries in which manual work, and especially manual work in manufacturing, is the growth sector of society and economy, that is, “Third World” countries with very large and still growing numbers of young people with little education and little skill. But […] there is a tremendous amount of knowledge work — including work requiring highly advanced and thoroughly theoretical knowledge — that includes manual operations. And the productivity of these operations also requires Industrial Engineering.

Still, in developed countries, the central challenge is no longer to make manual work productive — we know, after all, how to do it. The central challenge will be to make knowledge workers productive. Knowledge workers are rapidly becoming the largest single group in the workforce of every developed country. They may already comprise two-fifths of the U.S. workforce — and a still smaller but rapidly growing proportion of the workforce of all other developed countries. It is on their productivity, above all, that the future prosperity and indeed the future survival of the developed economies will increasingly depend.” — Peter F. Drucker, Management Challenges for the 21st Century (emphasis added)

Without acceptance of the fact that knowledge itself — regardless of its specific content — can, in principle, also be harmful, there are hardly any targeted solutions to this problem. In particular, the uncritical application of rationalization measures that proved successful in the field of manual labor is highly problematic.

And without an empirically valid understanding of knowledge (and Knowledge Quality) — one that does not move merely within symbolic regress — attempts at change tend to remain on the level of (usually ideologized) opinion debates.

Knowledge-related aspects are, after all, culturally anchored far more deeply than the romanticized notions of manual labor quoted by Drucker above.

The phenomenon of Qualitative Disinformation constitutes a central barrier to the intelligent organization of organizations. Passive Disinformation offers a culturally, politically, and ideologically neutral starting point for significant improvement. Addressing it opens up fundamentally new and simple solutions to the increasingly complex problems of knowledge work.

The Misery of Psychometrics

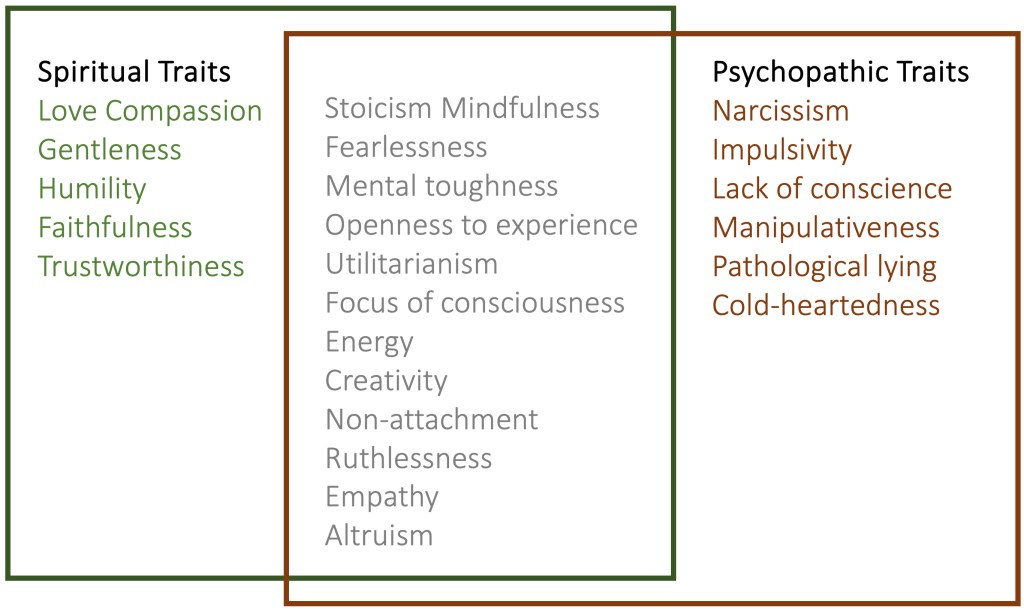

Saints are often hardly distinguishable from psychopaths: Kevin Dutton’s The Wisdom of Psychopaths provides an extensive collection of examples illustrating the misery of psychometrics.

In the attempt to measure personality (a.k.a. the soul), behavior and its causes are reduced to a system of symbols that is — inevitably — hopelessly overstrained.

The discussion could quickly end here, if only one were willing to accept that fact — but (usually confused) discussions are, after all, an essential lifeblood of the relevant disciplines.

The more drawers you fit into, the fewer you actually fit. Dutton, for example, offers the following ones:

Ultimately, psychopathy can be traced back to the inability to feel compassion.

In this sense, it represents one of the most fundamental manifestations of Qualitative Disinformation.

Disrupting Systems

„At the end of it software is art. And so just like an artist – if you lack creativity, if you lack that spark, you can have a corporation that hires as many inhouse artists as you want. You are never going to create great art, it will be soulless, it will be empty. And that’s what happens to innovation. When innovation is brought into large companies, it goes there to die.

When they send their employees to workshops and seminars to teach them how to think creatively […], innovation goes there to die. Creativity goes there to die. And if by some miracle an inspired creator arises from within the corporation, creates something truly unique, creative, disruptive, expressive, the entire mechanism of bureaucracy will stomp down on that idea and kill it very very quickly:

“Tommy, we love your idea and your creativity. This is really a fantastic invention you’ve brought to us. Now, we have conducted a focus group and assembled a committee, and we don’t want to interfere with your creative process. We have a few minor suggestions to help it be more broadly appealing among our customers and more in line with our strategic goals” – and that is the corporate sound of on creativity. By the time that idea comes out of committee it is a pale image, a skeleton of what it once was. And everything good and creative and wonderful about it has been sucked out […]

And every time they miss the point. And this happens again and again and you see it through history. […] what you see is corporate organizations and governments having innovation workshops, speaking about disrupting from within, and all of this empty talk.“ Andreas Antonopoulos: Thoughts on the Future of Money

At the end of it organization is like software.

But what is creativity?

“Everyone thinks himself a wonder” (Gracián).

Ultimately, what is needed is an empirical standard for Knowledge Quality.

Political Incorrectness

The internet can act like a good book — in that it makes the stupid more stupid and the intelligent more intelligent.

But above all, it dramatically increases complexity and renders organizational malfunctions ever more transparent.

As traditional steering systems decline, alternative ideologies emerge — and there is little that cannot become an ideology, or even a religion.

Where cognitive dissonances were once managed centrally, we now find quite similar decentralized forms of control. Yet where the dissonances become too strong, we see a return to even more rigid versions of the same old patterns.

Neither form will solve its basic problem without breaking The Ultimate Taboo — which also helps to mitigate conflicts between the opposing sides.

Everything else is mere randomness and symbolism.

Clash of Cultures

The organization of organizations is an (dis)information problem: the greater the informational advantage, the easier the control.

No one is all-knowing or all-powerful. Social systems emerge from the interactions of individuals who are, to varying degrees, limited (“trivialized”) and ideally compensate for one another’s weaknesses. However, the more degrees of freedom an individual has — and claims for themselves — the more difficult shared coordination becomes.

A certain degree of shared limitation was a key prerequisite for humanity’s cultural development beyond small-group size.

Göbekli Tepe (“the potbellied hill”) was built around 11,000 years ago and is considered one of the oldest known examples of the collective domestication of humankind.

The construction of this prehistoric sanctuary required an enormous collective effort without any immediately apparent practical benefit; its massive pillars weigh up to two tons.

The structure thus demanded a high level of coordination among hunter-gatherers, who at that time largely lived in small bands.

In honor of collective ideas that are now unknown, people alternated between working and celebrating (archaeologists have found remains of an early Oktoberfest-like event).

Ideology can have a highly trivializing effect and may foster the emergence and flourishing of strong organizational cultures.

However, even the most successful cultures are subject to a prisoner’s dilemma: while they expand individual possibilities, they also tend to level them out.

The benefits of trivialization reach their natural limits at the latest when external competition is less restricted — or when such systems simply can no longer be maintained.

The growing loss of trust in traditionally successful structures, media, and steering mechanisms today is due, not least, to the broader availability of information to the general public.

A quantitative informational advantage (see Ashby’s Law) is, however, only a necessary — and by no means sufficient — precondition for targeted and sustainable improvement.

In particular, organizational culture in the guise of system rationality (where “rational” means “serving the preservation of the system”) regularly eats even the best plans for breakfast.

Even the best new solution faces an uphill battle if it does not suit the old one — which, after all, should not come as a surprise.

How do you motivate someone to saw off the branch they are sitting on — whether imagined or real?

As long as the fundamental problem remains untreated, one loses oneself endlessly at the margins and in the confusion of organizational-cultural confusions.

If the foundation is strong, however, the ends can easily be mastered.

The most fundamental starting point is the empirical improvement of organizational knowledge.

The empirical phenomenon of Passive Disinformation provides the simplest possible access to Knowledge Quality — and offers a consensual, ideologically independent legitimation for a minimally invasive yet maximally effective break with system rationality.

Mens Sana

What only a few years ago still belonged to the realm of science fiction has, through the exponential progress of digitalization, now become part of everyday reality.

The successes of artificial intelligence seem almost magical — gradually disenchanting the uniqueness of human learning.

In fact, the design of highly capable neural networks is far simpler than one might assume (for a quick introduction to the basics, see here).

The further development of “real” AI is driven by massive economic incentives and extraordinary rewards for those involved. It cannot be stopped.

Those who impose restrictions on themselves must expect to be dominated — perhaps even rendered irrelevant — by the new competition.

Against this background, the founding of the first AI church was only a matter of time:

Anthony Levandowski’s officially recognized wayofthefuture.church is dedicated to the creation and worship of an AI god.

Meanwhile, the venerable Kodaiji Temple in Kyoto has created Mindar (mind-augmented religion), an artificial incarnation of the beloved Buddhist deity Kannon — whose human incarnation is regarded as the Dalai Lama.

Japanese crypto-Christians, incidentally, also venerate Kannon as the Holy Virgin Mary.

Digital disruption has thus reached one of the most deeply human domains: that of faith communities.

Levandowski justifies the inevitable divinization of the machine primarily from an economic perspective:

“There’s an economic advantage to having machines work for you and solve problems for you. If you could make something one percent smarter than a human, your artificial attorney or accountant would be better than all the attorneys or accountants out there. You would be [ … very rich ]. People are chasing that.”

What does this mean for the organization of organizations?

Even conventional operational management, when compared with financial management, is in many cases more art than science — due to the extreme challenges of complexity (and at times its kinship with faith communities can hardly be denied).

Enterprise Resource Planning has become a global multi-billion-dollar market whose implementation weaknesses become increasingly apparent the more complex the operational field becomes.

And attempts at complexity reduction through poor trivialization unfortunately have the unpleasant side effect of diminishing organizational intelligence.

The essential impairments of organizational control are rooted in disinformation — in the simplest case, already by the fact that planning processes, decisions, and organizational behavior measurements are decoupled from one another.

The primary fundamental problem to be solved, therefore, lies in the proper integration of organizational information systems: “If the foundation is strong, the ends can be controlled with ease.” — Musashi

Even well-intentioned control systems designed with this goal in mind — such as the Balanced Scorecard — tend to fail in practice due to inadequate integration, poor behavioral measurement (laden with hermeneutics and (micro)politics), and an overall lack of coherence.

Often, they are simply reduced to the limited scope of traditional financial control.

The first missing link toward solving the fundamental problem is thus a consistent, largely loss-free vertical integration of management information.

BubbleCalc makes a tangible contribution to closing this gap:

its radically simple algorithm enables cross-organizational integration of heterogeneous expert systems, further extended into a process-integration solution with BubbleHub.

With the addition of further control-relevant information, “organizational intelligence” can be significantly increased — provided the organization allows it (in many cases, even far more modest attempts at improvement fail due to system-rational resistance to change.

The case studies on the proliferation of process cultures and failed adaptation to new, disruptive competitors are so numerous that this topic has become almost uninteresting from an organizational-research perspective.)

Even the best technical solutions often break their teeth on the system rationality of deeply entrenched legacy cultures:

technical improvement is almost trivial compared with its sustainable implementation within an organization.

Ultimately, common sense — combined with a consensual legitimation for breaking with system rationality — represents the ultimate missing link for fundamental, empirically effective improvements.

Not least, a fundamental improvement of Knowledge Quality seems urgently needed from a societal perspective:

the totalitarian surveillance capabilities already available today far exceed anything Orwell could have imagined in his darkest nightmares.

The control principles that have proven highly successful over the past centuries no longer scale.

More evil arises from naivety and knowledge-romantic stupidity than from malice.

The hard-won democratic achievements of our cultural evolution may now be only one poor election away from their permanent end — regardless of which side prevails.

(The outdated distinction between “left” and “right,” inherited from the 19th century, is irrelevant in this context.)

Instead of new forms of machine-breaking — which would not work on a global scale anyway — we should address the far more fundamental problem.

Cybernetics & Intelligence

„Whether a computer can be „really“ intelligent is not a question for the philosophers: they know nothing about either computers or intelligence.“

„Many of the tests used for measuring „intelligence“ are scored essentially according to the candidate’s power of appropriate selection. […] as we know that power of selection can be amplified, it seems to follow that intellectual power, like physical power, can be amplified. Let no one say that it cannot be done, for the gene-patterns do it every time they form a brain that grows up to be something better than the gene-pattern could have specified in detail. What is new is that we can now do it synthetically, consciously, deliberately.“

— William Ross Ashby

Clash of Symbols

“One half of the world laughs at the other — and all are fools alike.

Everything is good, and everything is bad, as opinion wills it.

What one desires, another despises.

An unbearable fool is he who would order everything according to his own concepts.”

— Balthasar Gracián

Blind Spots Everywhere…

The metaphor of the blind spot is used in an almost unmanageable number of ways, most of which refer—more or less—to the physiological phenomenon, though the analogy often leaves much to be desired. Please judge for yourself; the following are a few exemplary alternative interpretations:

Zajac and Bazerman, for instance, regard errors of judgment as blind spots:

“Porter […] implies that [… the competitor’s assumptions about itself and about the other companies in the industry] may be strongly influenced by biases or ‘blind spots,’ defined as ‘areas where a competitor will either not see the significance of events at all, will perceive them incorrectly, or will perceive them very slowly.’ Knowing a competitor’s blind spots […] will help the firm to identify competitor weaknesses.” (Zajac, E. J.; Bazerman, M. H.: Blind spots in industry and competitor analysis: Implications of interfirm (mis)perceptions for strategic decisions, in: Academy of Management Review, Vol. 16, No. 1, 1991).

The following perspective might be called “holistic”:

“Then the distinction itself is the blind spot that must be presupposed as a condition of possibility in every observation. […] We have found the blind spot […] It is the distinction itself that must underlie all observation. But as a distinguishing designation, the concept of the observer is very abstract. It includes not only perceiving and thinking (knowing), but also acting. After all, purposes and values are distinctions as well, and therefore blind spots.” (Luhmann, N.: Wie lassen sich latente Strukturen beobachten?, in: Watzlawick, P.; Krieg, P. (eds.): Das Auge des Betrachters: Beiträge zum Konstruktivismus, Festschrift für Heinz von Foerster, Munich/Zurich: Piper, 1991, following Spencer-Brown, translated by me; here, in the final consequence, everything within a knowledge base becomes a blind spot).

Most commonly one finds differential (or “quantitative”) interpretations, as for example in the “Johari Window”. The blind spot corresponds to missing knowledge (in varying forms depending on the author).

Some authors combine differential and holistic interpretations, such as Maturana and Varela:

“All we can do is generate explanations—through language—that reveal the mechanism by which a world is brought forth. By existing, we generate cognitive ‘blind spots’ that can only be removed by creating new blind spots in other areas. We do not see what we do not see, and what we do not see does not exist.”

(Maturana, H. R.; Varela, F. J.: Der Baum der Erkenntnis: Die biologischen Wurzeln des menschlichen Erkennens, transl. by K. Ludewig, Munich: Goldmann Verlag, 1990, English transl. by me).

For further interpretations and a detailed presentation of my qualitative perspective, which is not limited to individuals, see Glück, T. R.: Blinde Flecken in der Unternehmensführung: Desinformation und Wissensqualität, Passau: Antea, 2002, pp. 31 ff.; or as an introduction: Glück, T. R.: Das Letzte Tabu: Blinde Flecken, Passau: Antea, 1997.

- An example by Russell, which is somewhat more difficult to grasp, concerns the set R of all sets that do not contain themselves as an element. If R is not contained in itself, must R then contain itself? ↩︎

- “For in order to define thinking, we would have to be able to think both sides of this definition (we therefore would have to be able to think the unthinkable).” Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus – Logisch-philosophische Abhandlung, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1989, Preface. ↩︎

- The notion fractal was originally introduced by the mathematician Benoît Mandelbrot. Mandelbrot used the term to characterise highly complex structures generated by the repeated application of astonishingly simple rules. Fractals can be regarded as dynamic equilibria. Thus, fractal geometry has become a symbol for numerous disciplines concerned with non-linear change. The fractal perspective of knowledge maintained here shows strong analogies to Mandelbrot’s conceptual foundation, which justifies the use of his term. ↩︎

- Economy, as “the science of rationality,” deals with the phenomenon of scarcity. Knowledge is a scarce commodity — particularly in the light of disinformation and informational asymmetries. An early principle of the economy of knowledge is attributed to William of Ockham (1285–ca. 1349) under the notion of Ockham’s Razor:

entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem — entities should not be multiplied beyond necessity; or, alternatively, entia non sunt multiplicanda sine necessitate. ↩︎ - The definition of “organization” is, in this context, deliberately broad and may refer to anything from the entire company to its parts, such as individual employees, teams, or IT systems. ↩︎

- Improvement must be defined according to context; it can also concern ethical questions. The economic (or rational) principle is essentially indifferent to ethics, though not unethical per se. It implies that any system of standards can be treated economically—this is not necessarily limited to monetary units. Empathy, as an ethical basis for action, must take into account that one’s perception of others’ suffering can be severely impaired by qualitative blind spots. ↩︎

- For example, through qualification measures, the employment of experts, or expert consultation. ↩︎

- This also involves aspects of micro-politics. ↩︎

- Keeping employees disinformed—or employing only disinformed employees—increases control and reinforces self-referential structures; however, it does not necessarily enhance organizational effectiveness. ↩︎

- This also implies correspondingly “deformed” communications which, at least formally, meet the requirements of knowledge transfer. Brunsson refers to the “hypocrisy” within organizations, which consists mainly of the disparity between talk and action. Argyris and Schön, accordingly, distinguish between “espoused theories” and “theories in action.” Coleman emphasizes that rational actors conceal their interests from one another behind a “veil of ignorance,” and so forth. ↩︎

- Cf. Glück, T. R.: Das letzte Tabu: Blinde Flecken, Passau: Antea, 1997. I have characterized these basic phenomena as “Qualitative Inhibition” or “the Qualitative Prisoner’s Dilemma.” Cf. Glück, T. R., Blinde Flecken in der Unternehmensführung: Desinformation und Wissensqualität, Passau: Antea, 2002 ↩︎

- According to Maturana, the best way to answer a question is to reformulate it according to the questioner’s level of intelligence. In this context, consultants are caricatured as people who take their clients’ watches in order to tell them the time. ↩︎

- This “haircutter” is a witty metaphor for the undifferentiated application of “cookbook rules.” It stems from the following joke: A man once invented an automatic haircutter. “This is the opening for the customer’s head,” he explained to the patent official. “With this dial, he can choose between short, medium-length, or long hair; with this lever, he can determine the type of cut; and after pressing the little red button, it takes no more than five or six seconds to achieve the desired hairstyle.” — “But people have different shapes of heads,” the official objected. “Only before the procedure,” replied the inventor. (Kirsch, W.: Strategisches Management: Die geplante Evolution von Unternehmen, Munich: Kirsch, 1997, p. 264.) ↩︎

- The quality of management is determined by the management of knowledge quality — particularly in the field of reorganization (fractal rationalization as the organizational enhancement of intelligence, understood as the improvement of knowledge quality through the reduction of qualitative blind spots), knowledge-quality certification, and integrative cultural development as an alternative to the undifferentiated installation of rigid organizational cultures that are difficult to reform (especially in cases of post-merger integration). Fractal knowledge-management tools and qualitative corporate and organizational governance are also included. The manager, as the most important management instrument, plays a key role — through qualification, auditing, and coaching, among others. ↩︎

- Luhmann, N.: Sthenographie und Euryalistik ↩︎

- Cf. Glück, T. R.: The Ultimate Taboo [Problems and Solutions] ↩︎

- And not even the naïve striving for “complete” control can change this; moreover: quis custodiet ipsos custodes? What we need is an ethically responsible, constructive handling of this basic restriction. ↩︎

- For the basic problem cf. Glück, What Is Knowledge. One – not very promising – approach entails contributing to a further proliferation of terminology and pseudo-patent remedies. The following joke is not quite new, but it captures the situation well:: “A drunk man is standing in the light of a street lamp constantly looking around on the ground. A policeman walks by and asks him what he has lost. The man answers: ‘My keys.’ Now they are both looking for them. Finally, the policeman asks if the man is really sure that he lost his keys exactly in this spot, but the man answers: ‘No, not right here, but over there – but there it is way too dark.” (Watzlawick, P.: Anleitung zum Unglücklichsein.) ↩︎

- “Where might be those who would dare to doubt the basis of all their former thoughts and deeds and who would voluntarily bear the shame of having laboured under misapprehension and blindness for a long time? Who is brave enough to defy the accusations which always await those who dare to deviate from the traditional opinions of their homeland or party? Where can we meet the man who can calmly prepare to bear the name of an eccentric, a sceptic, or an atheist, as it awaits all those who have even minimally questioned one of the general opinions?”

(Locke, J.: Über den menschlichen Verstand.) ↩︎ - Max Planck overstated this subject in his famous quotation: “A new scientific truth normally does not gain general acceptance by convincing its adversaries, who then admit to having learned their lesson. It rather gains acceptance by the fact that its adversaries are slowly dying out and that the new generation has been familiar with the new truth from the very beginning.” (Planck, M.: Wissenschaftliche Selbstbiographie.) ↩︎

- Thus, knowledge-qualitative evaluations can be made available for investment decisions. ↩︎

- In fact, everything depends on the definition of the problem. Cf. Glück, T. R.: The Ultimate Taboo: Problems and Solutions. ↩︎

- The goals need not be explicitly formulated. The totality of all effective — i.e., behavior-guiding — goals of an individual can be regarded as that person’s “personality.” Accordingly, culture can be interpreted as the personality of a society, an organization, or any other collective entity. ↩︎

- He who measures much, measures much mess — not everything measurable is meaningful. In the testing of scientific hypotheses, two basic types of error are distinguished: a Type I error occurs when a correct hypothesis is rejected; a Type II error occurs when an incorrect hypothesis is not rejected. ↩︎

- Friedrich Nietzsche ↩︎

- Christian Morgenstern: The Impossible Fact. ↩︎

- For an introductory overview, see the classic Parkinson’s Law, or, alternatively, Dilbert, et al. ↩︎

- Mintzberg, for example, has expressed criticism of the schematic, unreflective training by case studies at Harvard Business School: “There they read twenty-page case studies about companies they had never heard of the day before, and afterward they believe they know which strategy those firms should pursue. What kind of managers do you think come out of that? Incidentally, that used to be a competitive advantage of the Germans: no MBA programs!” ↩︎

- “Only part of the art can be taught; the artist needs it whole. He who half-knows it is always erring and speaks much; he who fully possesses it acts and speaks rarely or late. […] Words are good, but they are not the best. The best cannot be made clear through words. […] He who works only with signs is a pedant, a hypocrite, or a bungler. There are many of them, and they thrive together. Their chatter holds back the student, and their persistent mediocrity frightens the best away. The true artist’s teaching unlocks meaning; for where words fail, the deed speaks.” (Goethe, Wilhelm Meister) ↩︎

- Popper, for instance, called for political systems to be designed in such a way that incompetent leaders can cause as little harm as possible; of course, this carries the risk that nothing positive can be achieved either. ↩︎

- The longer such systems exist, the more impressive their self-justifications become: neither duration nor designation guarantees quality. ↩︎

- Thus, “organizational development” may in fact turn into organizational entanglement and further stabilize a culture of ineffectiveness. In this context, power is understood less as a potential for enabling action than as a potential for prevention—while intrigue and defamation serve as the actual instruments of control. ↩︎

- For an overview of fundamental approaches to problem-solving, see Glück, T. R.: The Ultimate Taboo ↩︎

- Einstein recommends making “everything as simple as possible—but not simpler.” Accordingly, only useless complexity should be reduced. ↩︎

- Normally, mixed forms occur, and most innovations consist in the (conscious or unconscious) reinterpretation or recombination of existing elements. As an example from management theory, one might cite Parkinson’s coinage “Injelitance.” “Injelitis” denotes the pathology of organizations arising from the rise of individuals who combine extraordinary incompetence and jealousy. “The injelitant individual is easily recognizable […] from the persistence with which he struggles to eject all those abler than himself, as also from his resistance to the appointment or promotion of anyone who might prove abler in course of time. He dare not say, ‘Mr. Asterisk is too able,’ so he says, ‘Asterisk? Clever perhaps—but is he sound?’ […] The central administration gradually fills up with people stupider than the chairman, director, or manager. If the head of the organization is second-rate, he will see to it that his immediate staff are all third-rate; and they will, in turn, see to it that their subordinates are fourth-rate. There will soon be an actual competition in stupidity, people pretending to be even more brainless than they are.” (C. N. Parkinson) ↩︎

- Goethe: “Only the scoundrels are modest; the brave delight in their action.” ↩︎

- You should not forget that learning can also leave you more stupid. ↩︎

- Knowledge that can be transferred through a “Nuremberg Funnel” should best be left to machines anyway. Computers process (not only) standardized information faster and more reliably—and have virtually unlimited storage capacity. ↩︎

- In this context, monetary value creation represents a special case. ↩︎

- The difference between theory and practice is smaller in theory than in practice. Pure theory, in isolating abstraction, assumes in the risk-return trade-off that the higher the expected gain, the higher the uncertainty one must accept 😉 ↩︎

- Speculative bubbles have always existed and will always exist. Illusions concerning the “true value” of goods (or of their substitute, money) have not emerged only since the invention of complex financial derivatives. ↩︎

© 2020-2025 Dr. Thomas R. Glueck, Munich, Germany. All rights reserved.