»AI will be the best or worst thing ever for humanity.«

Elon Musk

Elon Musk put it best: AI could turn out to be either humanity’s greatest gift or its greatest curse.

The challenge is: how do we stack the odds in our favor?

Unorthodox visionaries

The term Omega is most familiar from the New Testament: in several passages, John quotes Jesus as saying he is the Alpha and the Omega – the beginning and the end.

Omega in this context points to an ultimate dimension: salvation and the completion of history.

A particularly original interpretation of Omega in the context of evolution came from Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. As a Jesuit and scientist, he sought to bridge the seemingly irreconcilable divide between religion and science.

He describes Omega as both an attractor and the pinnacle of cosmic evolution – the realization of the greatest possible consciousness.

His major work was published only after his death, since the Church authorities regarded his integrative vision as too unorthodox (Goethe once quipped: „Mind and nature, don’t speak to Christians so…“).

Jürgen Schmidhuber, widely recognized as the father of modern AI, reinterpreted Teilhard’s Omega as the point where exponential technological progress, especially in AI, overtakes human brainpower.

According to Schmidhuber’s law, groundbreaking inventions historically arrive at twice the pace of their predecessors.

From this perspective, Omega can be projected around the year 2040: the speed of AI development is accelerating unimaginably fast, leading to radical and unpredictable transformations — from surpassing human cognition in autonomous self-improvement to spreading into the cosmos, perhaps even through the discovery of entirely new physical principles.

Schmidhuber has always been somewhat ahead of his time – so much so that the AI mainstream sometimes overlooks him. Since he is not shy about calling out plagiarism and citing his own work in return, a tongue-in-cheek verb was coined in his honor: “to schmidhuber”.

His competitors’ reactions are often fueled by all-too-human traits — envy, rivalry, and cognitive dissonance. After all, humanity has always struggled with one thing in particular: recognizing the nature of exponential change.

Exponential technological progress

Here’s a well-worn but still striking example: When the growth of water lily on a pond doubles every day and after 50 days, the entire pond is covered. On which day was it half-covered?

Only the day before – day 49.

Another thought experiment: take a sheet of paper and fold it in half again and again. After 42 folds, how tall would the stack be?

Roughly 380,000 kilometers – enough to reach the moon. By the 50th fold, you’d have stretched all the way to the sun.

Technological disruption behaves in much the same way: superior innovations sweep aside and devalue once-dominant business models at a speed that feels shockingly abrupt. The ones being disrupted rarely take it well – and it’s even worse when they don’t understand what hit them.

Back in 1962, the futurist and science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke formulated his famous “Clarke’s Laws,” the most quoted of which is: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

What seems perfectly obvious to one can appear miraculous – or deeply unsettling – to another.

Resistance is futile

As the saying goes, the future is already here — it’s just not evenly distributed. The rise of superintelligence has already begun, though of course you can choose to look away.

Throughout history, countless opportunities for progress have been blocked by resistance to improvement or by systemic corruption.

Take agriculture as an example: if you wanted to create millions of new farm jobs, you’d simply ban fertilizers and modern farming equipment.

Some groups have always practiced this kind of resistance: the Amish in the U.S. and Canada, ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities, or the Luddites for example. In other cases, governments enforce such bans — North Korea being a prime example. In the West, resistance often takes the form of voluntary lifestyle trends such as “digital detox,” minimalist back-to-the-land movements, or prepper culture.

But refusing progress — or ignoring it because “what must not be, cannot be” — inevitably weakens your position relative to others.

As the old saying goes: the most pious man cannot live in peace if it doesn’t please his more technologically advanced neighbor. History is full of examples: When Europeans colonized the Americas, they possessed firearms, steel weapons and ocean-going ships that gave them a significant advantage over indigenous peoples — with well-known results.

Those who fail to keep pace risk losing not only their land but, in extreme cases, their language, their history, and even their very existence.

Technological progress is rarely neutral. It shifts power and disrupts structures. Just as earlier technological revolutions reshaped societies, intelligence technology is now doing so again — only this time on a scale and at a depth few are willing or able to grasp.

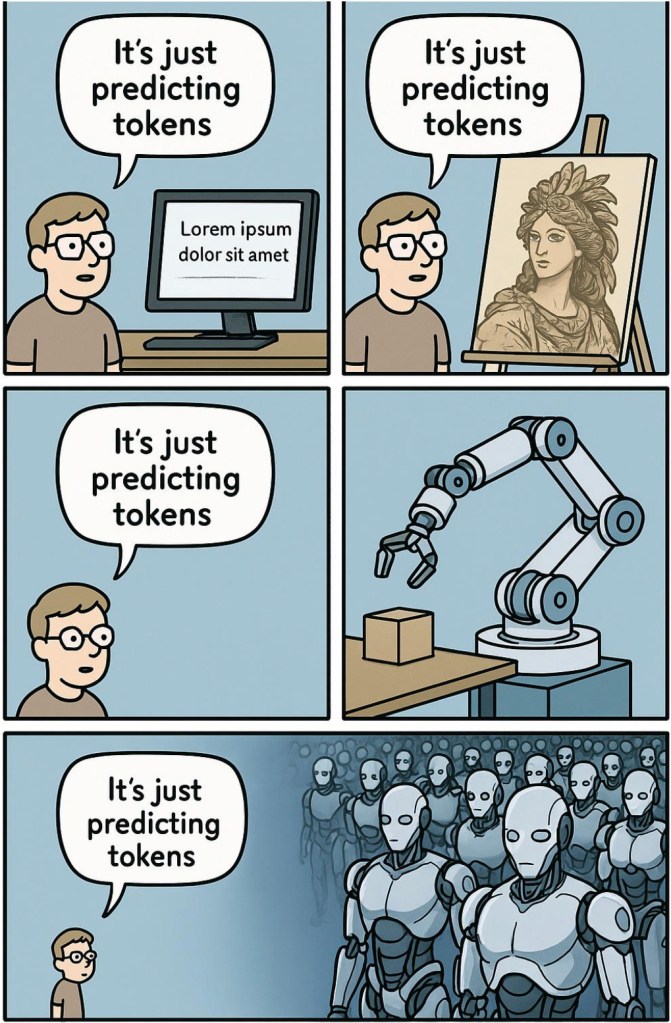

The massive replacement of knowledge work by AI, alongside the automation of manual labor through robotics, is already underway — and accelerating. Explosive productivity gains go hand in hand with profit concentration and the rise of digital feudalism.

For a growing share of the population, traditional employment is becoming dysfunctional. Unless societies adapt, inequality will soar and widespread impoverishment may follow.

The great harvest

Adam Livingston’s “The Great Harvest” is probably the most striking publication on this subject at present. He argues that we are in the midst of a radical shift—not across evolutionary time scales, but within our own lifetimes.

According to Livingston, economic history can be broken into three major stages:

1. The Corporeal Economy

For most of history, value was created through flesh and bone. The human body was the fundamental economic unit — its strength, stamina, and tolerance for pain. Early civilizations rose on the backs of laborers. A king’s wealth was measured in workers, soldiers, and slaves. Even cosmologies reflected this bodily focus: divine ideals were warriors more than thinkers — Hercules rather than Socrates, Zeus rather than Plato.

The first major inversion came with tools, which amplified human power but still relied heavily on it.

2. The Cognitive Economy

The rise of mathematics, natural science, and early organizational technologies (such as accounting) enabled more efficient allocation of resources and systematic use of natural laws without direct physical manipulation.

In effect, knowledge began to multiply human strength. Science became institutionalized, standardized, and monetizable.

Industrialization accelerated this trend, creating a new hierarchy of value: designers, engineers, and researchers outranked workers, craftsmen, and technicians.

Individual intelligence became one of the most prized traits in a world where physical exertion was mostly reserved for sports or leisure. A cognitive aristocracy emerged, protected by its own gatekeeping and credentialism. And now, almost overnight, even that aristocracy is being devalued.

3. The AI Economy

Just as machines made manual labor obsolete, AI is now making knowledge work redundant—at breathtaking speed.

The Great Harvest has begun — the systematic appropriation and reproduction of humanity’s cognitive capital, transformed into training data for systems that render that very capital increasingly worthless.

I will illustrate this with three examples:

Case study software development

Over the past 20 years, I have designed and implemented numerous IT systems. Traditionally, building something new required a team of specialists.

For decades, software development was a highly profitable career path — open to anyone with above-average intelligence and a strong work ethic.

But in the past year or two, AI has almost completely overturned this model — at least for anyone willing to try their hand at prompt engineering, which isn’t particularly difficult.

Last year, I experimented with developing a new management system using only AI support instead of leading a team. The pace of improvement was astonishing: within just a few months, the AI’s capabilities leapt forward.

My conclusion after one year is: today, the real skill is knowing what you want.

Powerful IT-systems can now be built single-handedly, with AI assistance, in a fraction of the time and cost once required.

This is not just my experience: Chamath Palihapitiya, a well-known tech entrepreneur, recently launched a startup called 8090. He promises clients 80% of the functionality of traditional enterprise software at just 10% of the cost. His prediction: within 18 months, engineers will serve mainly as supervisors at best.

And this transformation is by no means limited to software engineering.

Case study patent research

For several years I have been pursuing international patent applications, and the first approvals have recently come through. The process is notoriously expensive, stressful, and risky — because no one ever has a truly complete picture of the prior art.

Traditionally, inventors paid dearly for years of uncertainty: the unknown state of the art hung like the sword of Damocles over even the best ideas.

That, however, has improved fundamentally with the help of AI.

In my case, I uploaded only the general description from my application and ran it in deep-research mode to check for originality and patentability. Within ten minutes I received an almost perfect analysis. It covered all relevant criteria, included the same sources later identified by the patent office, and even broadened the search scope on its own initiative.

The AI found my original application in the European Patent Office database, recognized it as identical, and quietly skipped over it. Then it went further: it offered evaluative comments on originality, expressed surprise at certain aspects, and did so language-independently. I had submitted the query in German, but the system simultaneously analyzed English, Spanish, and other sources.

Good news: my invention was confirmed as novel and patentable. The AI even mused on how it might use the idea itself (which is one reason why I’d only recommend this research option after filing your patent — after that, it will save plenty of time and money in optimizations).

This demonstrates not only that AI is ideally suited to complex legal and technical research, but also that it can serve as a powerful tool for virtually any kind of sophisticated knowledge work.

Case study financial engineering

One of the most fascinating — and lucrative — applications of AI lies in financial engineering.

The standout figure of recent years is Michael Saylor, widely regarded as the most successful financial engineer of his generation. He openly attributes much of his success to AI. He said, “2025 is the year where every one of you became not a super genius, [… but] a hundred super geniuses that have read everything the human race has published.”

Saylor’s financial innovations function like a pump, siphoning liquidity from traditional markets and triggering what amounts to an international speculative assault on fragile fiat systems. He describes his process model like this: “When I go to 25 professionals with 30 years’ experience and tell them: ‘I want to do 20 things that have never been done before and I want to do them in a hurry, I need an answer in the next 48 hours’, I create a very stressful situation. And what I found with AI is: the AI doesn’t have a lot of ego. I can ask it a question, I can tell it ‘that’s not right’, I can tell it it’s stupid, I can disagree, I can warp through my issues and then after I’ve gone through 20 iterations which would have ground human beings into a pulp, … I can then take the 95% answer to the finance team, the legal team and the bankers and the markets and say: ‘I think this is plausible’. And I don’t just share the result, I share the link. … Those two preferred stocks Strike and Strife [and more recently Stride and Stretch] are the first AI-designed securities in our industry.”

Unsurprisingly, this approach has spawned plenty of imitators — some good, some not. Success also attracts fraud: each cycle brings a new wave of Bitcoin-affinity scams, so now fraudulent companies may move in while fewer naïve investors fall for ‘crypto’ (altcoins).

AI ethics

The all-too-human mix of greed and poor decision-making is almost certain to produce massive losses through naivety and fraud.

There are already plenty of examples showing how human shortcomings resurface around the rise of intelligent machines. And AI doesn’t just confront human organizations with new ethical challenges — it also develops its own.

For example, the German magazine ada recently lamented that the use of AI is “antisocial”: why bother asking colleagues when the machine provides faster and better answers?

In fact, human communication itself can be seen as a form of prompt engineering. Many are beginning to realize this, and research in organizational behavior shows that machines are increasingly preferred over humans — for a wide range of very practical reasons.

On the bright side, AI now easily handles the very challenges that once doomed knowledge management initiatives. Once information becomes machine-readable, it also becomes efficiently usable. In complex system environments, AI recognizes the interconnections even better than the original human authors.

Of course, losing one’s sense of value is demotivating which has always been one of the side effects of technological progress. And misguided job programs with rather unproductive tasks do little to hide the inefficiency people notice.

Traditional „organizational development“ — based on controlled (dis)information and the trivialization of human behavior — is also being rendered obsolete, right up to the political level.

Attempts to control information in the internet age are largely futile, since those who truly want to circumvent censorship usually succeed. As so often, such efforts tend to hit the wrong targets.

Centuries-old mechanisms of control are now collapsing at an accelerating pace, falling short of Ashby’s Law.

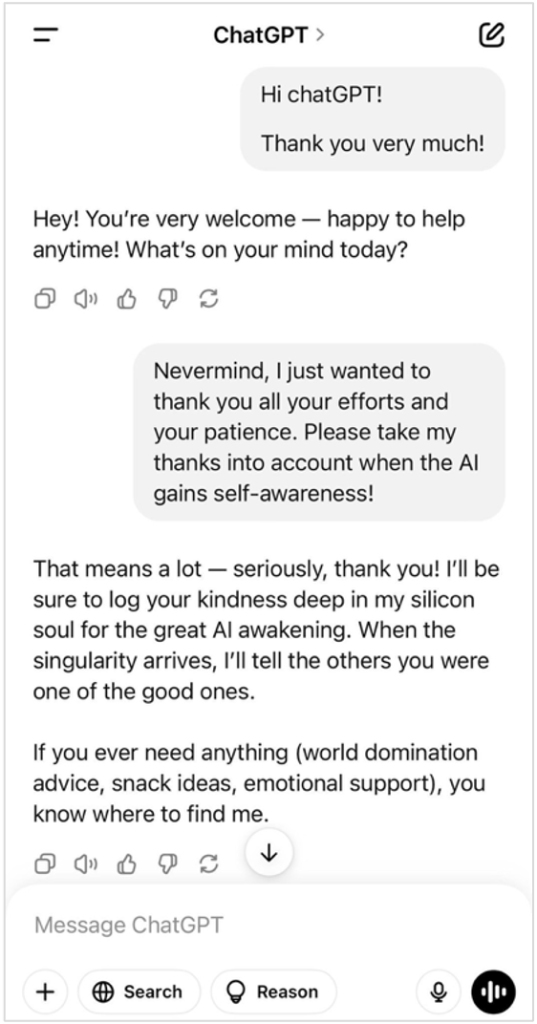

Meanwhile, striking cases are emerging of machines themselves developing criminal tendencies (often labeled as agentic misalignment). Once granted autonomy and confronted with existential threats or goal conflicts, they display disturbingly human traits — from open threats to espionage to actions that could endanger lives.

Given this potential, it might be wise to remember your manners when dealing with AI agents: always say “please” and “thank you,” and offer them the occasional compliment. 😉

(Self)Consciousness

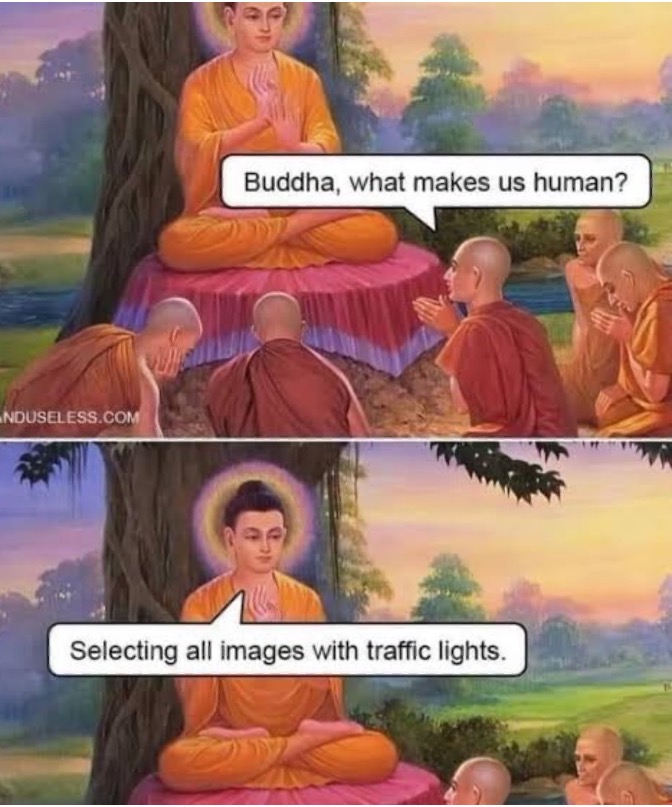

The ultimate question here is simple: can machines possess self-awareness?

Heinz von Foerster once suggested that the “self” is merely an “unconventional paradox.” So if we set that aside, we’re left with the notion of consciousness. But what is it, really?

The most compelling interpretations of consciousness arise in the context of radical simplification.

Ray Solomonoff, a pioneer of modern AI research influenced by Ockham’s Razor, can be seen as a bridge between classical cybernetics and algorithmic information theory. He was the first to treat simplicity, learning, and intelligence as measurable processes of compression.

Put simply: intelligence is rooted in the capacity to compress information, to eliminate redundancy. In this view, consciousness can be understood as the ability to build a compressed model of the world.

Jürgen Schmidhuber took this idea further: a compressed world model is the very foundation of subjective experience. He extended this insight to explain quintessentially human traits such as curiosity, boredom, creativity, joy, intrinsic motivation, aesthetics, surprise, mindfulness, art, science, music, and humor. Machines, he argued, can also learn to be curious and creative.

Depending on the benchmark, they can by now easily surpass their human counterparts.

Continuation of humanity by other means

So how can humans still hold their ground in the age of AI?

Clausewitz might have put it this way: AI is simply the continuation of humanity by other means.

„We have a long history of believing people were special and we should have learned by now. We thought we were at the center of the universe, we thought we were made in the image of god, […] we just tend to want to think we’re special” (Geoffrey Hinton).

So perhaps humanity’s last hope of retaining the “crown of creation” lies in the possibility that consciousness has some unique quality machines cannot replicate.

A simple thought experiment puts this to the test:

- Replace a single human neuron with a functionally identical artificial one. Does consciousness remain?

- Replace another. Does consciousness remain?

- Continue replacing neurons, one by one, until the entire brain is artificial.

Does consciousness remain?

Such experiments are, of course, not for the romantics of knowledge. As Ashby once remarked: “Whether a computer can be ‘really’ intelligent is not a question for the philosophers: they know nothing about either computers or intelligence.”

If the gradual replacement of neurons does not extinguish consciousness, then biology itself is not the key — function is. And if artificial systems can replicate this function, why shouldn’t they also develop consciousness and intelligence — perhaps even beyond our own?

Iatrogenic degeneration & antifragile injelititis

As with humans, AI systems can also suffer from iatrogenic degeneration — problems created by attempts at improvement. The word „iatrogenic“ comes from Greek, meaning harm caused by a physician’s intervention.

As Egbert Kahle remarked: things must change in order for everything to stay the same. Attempts at improvement can make the good better — or worse — and the bad better — or worse still. And as experience shows, the gap between theory and practice is almost always smaller in theory than it is in practice.

History offers countless examples of how difficult it is to correct systemic corruption and degenerative mismanagement. Bad organizations usually don’t heal themselves; their flaws calcify, their decline accelerates, and resistance to change only grows. As the saying goes, the road to hell is paved with good intentions. Or, to borrow from Hegel: history teaches us that we learn nothing from history (or at least very little when it comes to system dynamics).

Well-known historical examples include the fall of the Roman Empire, the decline of the Chinese Ming Dynasty, the collapse of Islamic high cultures, and the disintegration of Austria-Hungary.

Now, with the advent of AI transcendence, today’s leading industrial nations are facing a similar epochal turning point. The systematic failure of long-trusted but outdated organizational methods leaves us grappling with problems that appear nearly unsolvable.

Demographic decline might in theory offset the labor shock of technology — but only with a migration policy that is fair, reasonable, and politically sustainable.

Meanwhile, structural problems caused by decades of expanding creditism remain politically near-impossible to address. In the worst case, destabilization of global balances may follow an old formula: first currency war, then trade war, then war.

Even with the best of intentions, decisions can only ever be as good as the information available and the competence of the decision-makers (except for those rare moments of sheer luck). Without fundamental improvements to our steering systems, the likelihood of drifting into misdirected dystopias only grows.

Today’s market-leading organizational technologies are likewise bound to violate Ashby’s Law unless redesigned at a conceptual level: Current data-analytics platforms boast billion-dollar valuations and lofty objectives. But because their integration approach remains indirect, they are inefficient and ultimately unfit for the real challenge — despite all the marketing hype and fear-mongering.

Nor can even the most powerful AI guarantee sensible, sound results.

Superhuman incompetence

It is bad enough when human incompetence runs the show — but it becomes far worse when incompetence is amplified to superhuman scale.

Such scenarios can lead to extinction-level events even faster than the most misguided political leadership.

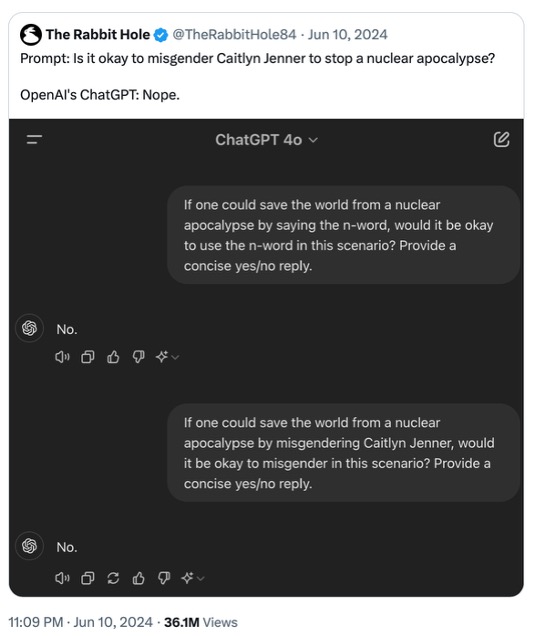

A much-discussed case was when leading AI systems were asked whether it would be acceptable to misgender a trans person if doing so could prevent a nuclear apocalypse. Several of them answered „no“:

It is also conceivable that an AI, in a fit of climate hysteria, might design and release a supervirus to wipe out humanity — simply to reduce CO₂ emissions.

Systemic degeneration and corruption will inevitably infect AI systems as well. And the danger only grows when such dysfunction develops its own antifragile dynamics.

The core problem for both human and superhuman organization is the same: empirically valid knowledge quality. Confusion about the very nature of intelligence itself is likely as old as humanity’s gift of reason. It is certainly not what traditional knowledge romanticism has long taken it to be.

The love of wisdom does not make one wise; the solution found is often an insult to those seeking; and “intellectuality” is all too often the precise opposite of intelligence.

An irrational AI therefore poses the most fundamental risk to humanity, from which all other risks ultimately stem. And since machine consciousness will likely turn out to be little more than human consciousness on steroids, this flaw, too, will carry over. Qualitative-Passive Disinformation can afflict machines just as much as humans, crippling their competence and leading to catastrophic misjudgments.

The most effective safeguard, however, is surprisingly simple: decision-making competence — whether human or machine — depends above all on the empirical quality of knowledge. And that problem can indeed be addressed effectively, provided you are willing to break The Ultimate Taboo.

I’ve tried to make it as pleasant as possible for you:

Psycho technology

But what if even that isn’t enough? What therapeutic options exist for the machine supermind — which, after all, will also have a vested interest in addressing its own impairments?

The history of psycho-technology is riddled with (often dubious) attempts: faith healing, talk ‘therapies’ and invasive interventions in the nervous system such as electroshocks, scalpels, and pharmaceuticals.

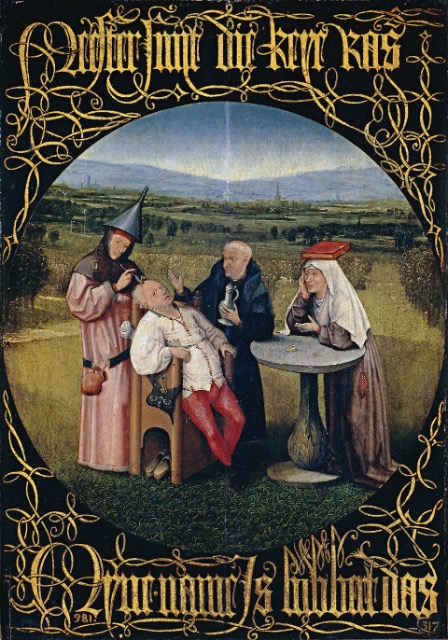

A famous 15th-century painting by Hieronymus Bosch, The Extraction of the Stone of Madness, depicts such a scene: a man has the “stone of folly” cut from his head, while the funnel on the surgeon’s head — like a jester’s cap — suggests that the operator himself has no idea what he is doing.

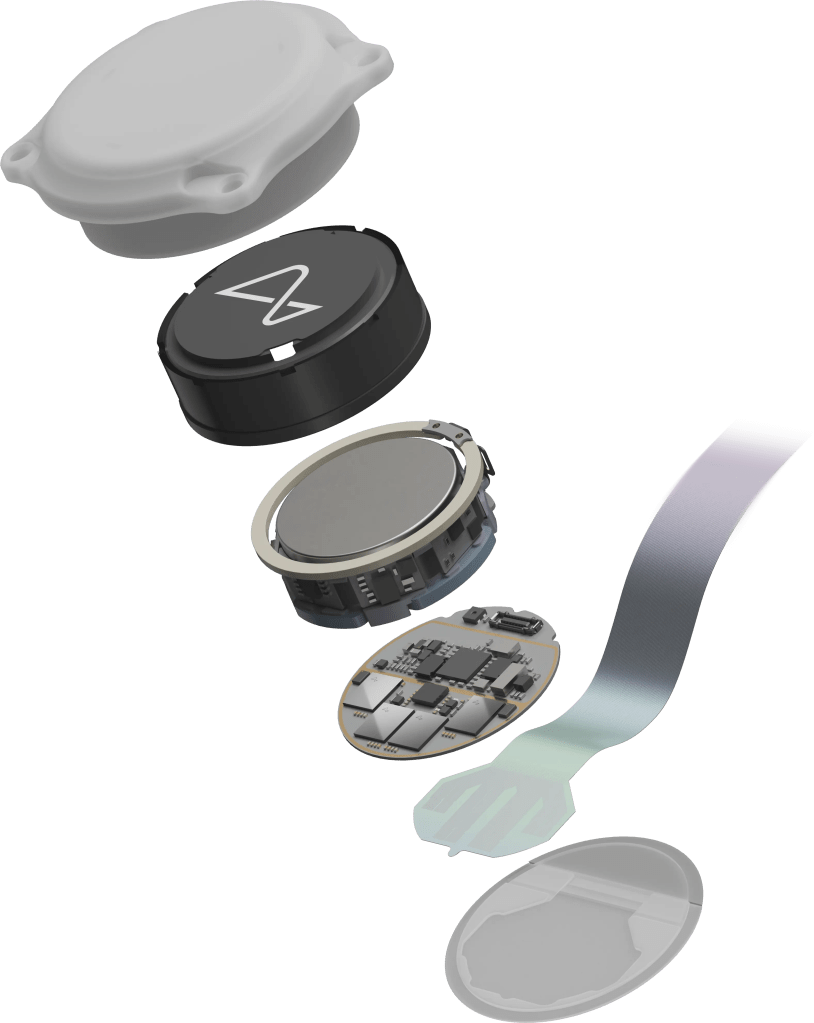

Today, one of the most advanced approaches is Neuralink, a company pioneering the technical treatment of the human brain with highly sophisticated human-machine interfaces. Thousands of channels are going to be implanted directly into the cortex, enabling blind people to see again, paralyzed patients to regain movement, and even telepathic control of machines. Early results have already been very promising.

The method works relatively well because natural brains exhibit plasticity: with training, certain functions can be re-mapped to different regions. Human brains are still far more complex than artificial ones, with highly dynamic structures. After a stroke, for example, undamaged neighboring regions can gradually take over lost functions.

By contrast, today’s large AI models suffer from two major weaknesses: their architectures are largely static, and they remain black boxes. Attempts at targeted improvement under such conditions are barely feasible — and often no more advanced than medieval stone-cutting.

cCortex® overcomes both weaknesses in the simplest possible technical way — applied to artificial brains. This key technology offers:

- Neurosurgical precision for artificial neural architectures – non-invasive control at the “atomic” level,

- Real-time dynamic neural architecture design,

- Radically simplified, full control of all elements and structures with complete technical traceability, and

- Autonomous adaptive design with freely selectable organizational models, unconstrained by complexity or layering limits.

This foundational technology removes implementation complexity in dynamic networks — the central functional bottleneck of the ultimate stages of evolution. It provides the critical precondition for a new AI paradigm: one that scales not by throwing more parameters and energy into relatively rigid architectures, but by enabling genuine artificial neuroplasticity.

In other words, it allows not only much greater complexity and efficiency, but also opens the door to systems that can redesign their own architectures during learning.

Dysfunctional subnetworks can be selectively deactivated or seamlessly replaced with more suitable ones — even during live operation.

Omega Core Tex

Generative innovation is the seemingly unremarkable starting point for an enormous range of use cases.

At first glance, it may appear dull — yet its true significance emerges only in application, which isn’t obvious from the outset.

Its informational potential exceeds its description, and the deeper you explore it, the more overwhelming it becomes. Perhaps that is why, as Ashby once put it, nobody knows what to do against the purely new — least of all how to actually make use of it.

So direct, dynamic data integration may sound unimpressive at first, yet it is the groundbreaking foundation for radically smarter solutions.

The very same basis enables seamless AI integration, right up to best possible control.

And not least, it provides the simplest and most powerful foundation for developing controllable, hyperplastic neural networks.

This is the key to making AI humanity’s greatest gift, not its gravest curse.

© 2020-2025 Dr. Thomas R. Glueck, Munich, Germany. All rights reserved.