»To study the self is to forget the self«

Dōgen

Among the oldest1 and perhaps the most fundamental of all questions is not where we come from or where we are going, but the simplest yet most difficult one: what is knowledge?

The challenge in answering this question lies in the fact that the very instruments we use are themselves constituted by knowledge.

Instead of finding genuine solutions, thought has produced ever more thought parasites, multiplying endlessly in confusion. It’s reminiscent of this slightly altered nursery rhyme:

One should know that thoughts have fleas

Upon their backs to bite ’em.

And the fleas themselves have fleas,

And so ad infinitum.

Progress in understanding has long been confined within narrow boundaries — sterile, self-referential discussions of “knowledge romantics”.2

Romance, after all, is unfulfilled love — for a reason.

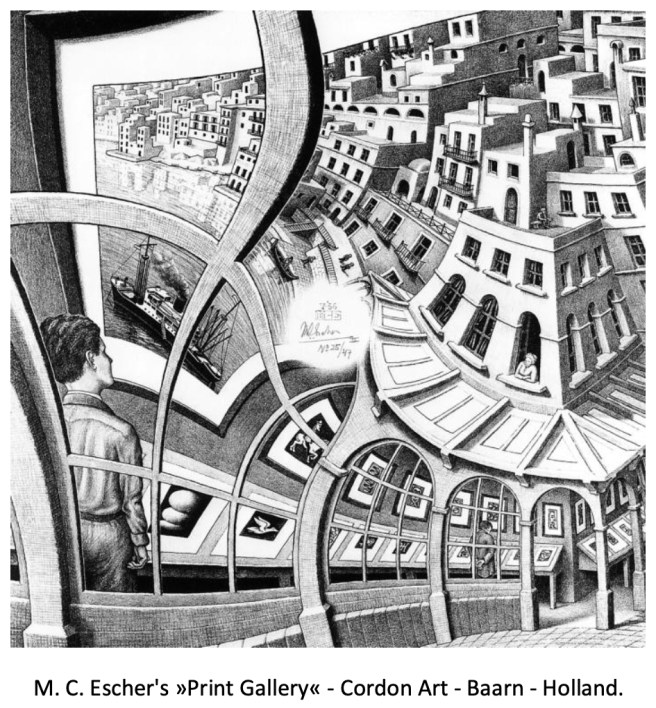

Wittgenstein, like all philosophers and their followers, inevitably suffered from his own prison of thought. Yet he left us perhaps the most beautiful metaphor for this condition — which I used as the opening quotation of my first publication The Ultimate Taboo, alongside M.C. Escher’s Picture Gallery:

A picture held us captive.

We were not able to escape,

for it was in our language,

which seemed only to repeat it relentlessly.

Wittgenstein

At times, even the most intractable problems can be radically simplified through inversion — by reformulating them in their dual form. This represents a fundamental shift of perspective.

This path out of the misery of knowledge romanticism can also be found in Wittgenstein (and, in traces, among other thinkers of his kind). Yet he, too, never truly escaped his own conceptual fog. In a lucid moment, he formulated the only direction that could meaningfully point toward a solution — though he continued to suffer from his mental confinement throughout his life which is all too obvious if you’re reading his texts:

“To draw a limit to thought, we should have to be able to think both sides of this limit (we should therefore have to be able to think what cannot be thought).”

I also adopted this statement and slightly adapted it:

To draw a limit to knowledge, one must know both sides of that limit — one must know what one cannot know.

Yet this dual approach, taken alone, remains nonspecific and empirically invalid.

At best we end up knowing that we know nothing — but does that really take us further? Hardly.

Niklas Luhmann, for example, suspected that any theory of cognition capable of addressing this problem would “presumably take on forms quite different […] from an epistemology of the classical kind.”

So what is still missing in order to make knowledge truly measurable and shapeable — empirically, not merely symbolically?

The concrete measurability of qualitative deficiencies offers the best approach.

The mother of all qualitative deficiencies of knowledge can, on the one hand, already be an integral element of the search just described; on the other, it may also exist in isolation.

I have called it Passive (or Qualitative) Disinformation.

It exists wherever a non-identical, model-based representation cannot be seen as a model. I’ve characterized its fundamental effects as qualitative prisoner’s dilemma — one possesses knowledge but is at the same time possessed by it — and qualitative inhibition.

The consequences are far-reaching and profound, yet they can now, for the first time, be addressed effectively at their source.

This Passive-Qualitative Disinformation represents the missing link that, together with the inverted formulation of the problem, enables an empirically valid, concretely measurable, and truly improvable quality of knowledge.3

It can be applied to virtually all information- and knowledge-based domains — and brings the endless romantic discourse on knowledge to an abrupt (and relatively painless) end.

This fundamentally new approach4 to system design and problem-solving is free from mysticism and other “-isms.” It is ethically, politically, and ideologically neutral — and therefore universally applicable. After all, what isn’t knowledge-based?

It is not sociology, not philosophy, and no longer an unfulfillable love affair.

On one hand, knowledge becomes empirically measurable and qualitatively shapeable; on the other, all its aspects — not only the pleasant ones — become visible.

It is not an ideology. It requires no esotericism, no politically tinted belief system, but instead a radically simple, generative, purely empirical approach.

It calls for neither inflated “meta-levels” nor elaborate theoretical constructs — and certainly no prior scholastic initiation. It merely asks to be applied — with open eyes and a free mind — insofar as one’s own qualitative blind spots allow.

This offers the most fundamental and simplest starting point for true improvement, and not just for organizations.

The path is not only radically simple — its effective application also enforces radical simplicity, preventing a relapse into traditional weaknesses.5

Hardly anyone lacks an opinion about what the quality of knowledge is or should be — which makes the ground beneath such discussions quite unstable.

To delineate my conceptual space more clearly, I deliberately chose the idiomatically uncommon term “knowledge quality” instead of “quality of knowledge”.

Yet even here, the risk of mix-ups remains high.

To emphasize the independence of my approach, I subsequently abbreviated knowledge quality as KQ, and use the phonetic code kei kju: for naming my concept.6

By consciously occupying a linguistic gap, KEI KJU becomes a strong, distinctive sign in this context7 that remains sustainable across consulting, training, software, and methodological contexts. Its phonetic similarity to certain Asian syllables is intentional.

Beyond its direct reference to a fundamentally new, axiomatic-empirical approach to knowledge quality, these syllables also carry positive associations in Asian contexts — such as respect, system, order, quality, and wisdom, combined with dynamism and clarity.

- »However the question was not, of what there is knowledge, nor how many different kinds of knowledge there are. For we didn’t ask with the intention of enumerating them, but to understand knowledge itself, whatever it may be. […] If somebody asked us about something completely ordinary, such as the nature of clay, and we answered him that there are different kinds of clay, e.g. for potters, for doll-makers or even for brickworks, wouldn’t we make ourselves look ridiculous? […] First of all, by assuming that the questioner could understand the matter from our answer if we simply repeated: clay – even with the addition: clay for the doll-maker, or any other craftsman. Or do you think somebody might understand the notion of something of which he doesn’t know what it is? […]Thus someone who doesn’t know what knowledge is will not understand the ›knowledge of shoes‹ […] It is therefore ridiculous to answer the question: what is knowledge? by mentioning some science […] That is like describing a never-ending way.«

Plato: Theaetetus, transl. by F. Schleiermacher, Frankfurt am Main: Insel Verlag, 1979, pp. 17 ff. ↩︎ - “whether [… s.o./sth.] can be ‘really’ intelligent is not a question for the philosophers: they know nothing about […] intelligence.” (Ashby) ↩︎

- The basic research of my dissertation project revolved around this very question, explored in organizational, decision-making, and (organizational) psychological contexts. There I developed a universally compatible, radically simple generative concept whose empirical character was already embedded in its axioms — a kind of axiomatic empiricism, or empirical axiomatics. And what could be more empirically valid than the investigation of non-identity between entities? This approach also serves as a nice example of the Inventor’s Paradox. The conceptual leap cost me many sleepless nights in my early 20s. ↩︎

- My approach provides a fundamental counter-design to traditional organizational development based on trivialization and injelitance (or to “self-organization” modeled after ant colonies etc.). It establishes a development platform that fosters genuinely more capable, intelligent, and performance-appropriate organizations instead of bureaucratic degeneration. ↩︎

- As a design-specific side effect, this approach not only justifies creative height with ease but also makes plagiarism extremely difficult. In such works, only copyright law applies — a rather weak form of protection that can easily be circumvented by generalization, “side moves,” or “arabesques” (cf. Vischer). But how could you find a “meta-level” here that would not contradict itself and vanish into the old fog? ↩︎

- This transforms an unwieldy expression into a concise, internationally usable brand. It allows for versatile design interpretations — through parentheses or typographic variations — and thus creates room for visual brand development. ↩︎

- not to be confused with the Japanese railway brand… ↩︎

© 2020-2025 Dr. Thomas R. Glueck, Munich, Germany. All rights reserved.