electric light did not come from the continuous improvement of candles.

Any status quo exists because it has prevailed in its context and is supported by its infrastructure. It is therefore context-dependent — if the context were different, the status quo would be different as well.

This is why dominant improvement potential often only becomes visible once the necessary infrastructure changes are also taken into account.

Truly effective improvements disrupt steady-state systems, which explains why they have always been met with resistance. Ayn Rand illustrated this vividly:

“Thousands of years ago, the first man discovered how to make fire. He was probably burned at the stake he had taught his brothers to light. He was considered an evildoer who had dealt with a demon mankind dreaded.”

New technologies typically suffer until suitable infrastructures emerge — usually driven by sufficient pressure or incentive. Once established, these infrastructures not only make the new technology usable but also enhance the performance of older ones and enable entirely new applications. Antonopoulos et al. referred to this as infrastructure inversion.

A classic example is the automobile, which initially performed poorly compared to horse-drawn vehicles on unpaved roads.

One favoring factor was that cities with increased traffic volumes were at some point in danger of drowning in horse manure:

Without the invention of the automobile, attempts at a solution would probably have consisted only of developing better horse manure disposal systems, e.g., by means of conveyor belts along the roads.

Improvement concepts can take a very long time for their practicable implementation if the necessary infrastructure is still lacking: for example, many already well-known innovations were only made technologically possible with an exponential increase in computer performance.

An interesting example is the development of graph theory by Leonhard Euler in the 18th century, for which, after more than 200 years, a powerful technological infrastructure is now available in the form of market-ready graph databases, which will dominate the relational (i.e. table-based) database systems that have led the market in many use cases so far: relational databases have considerable difficulty with relational complexity, which severely limits their application possibilities in this respect and also massively impairs organizational design compared to graph-(i.e. network-)based systems.

Organization depends on control information, which in practice is regularly distributed across different systems and requires significant trade-offs for overarching integration.

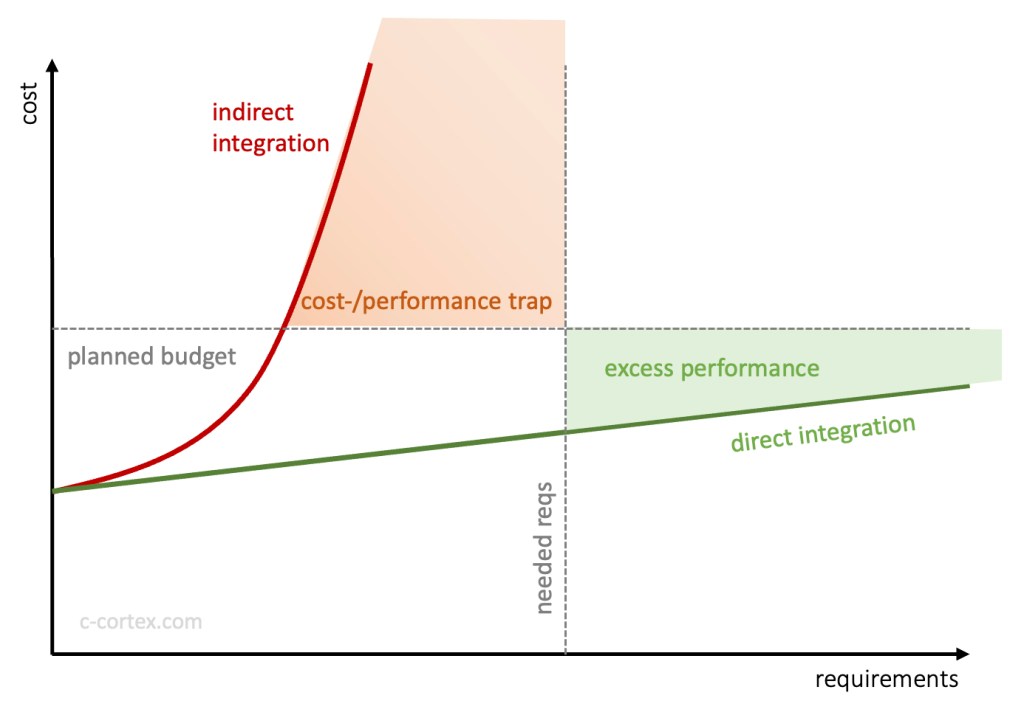

Indirect attempts at integration using the old infrastructures are quite similar to the aforementioned horse manure conveyor belts.

Especially the attempt to integrate systems and improve organizational design on a non-graph, indirect basis is therefore mostly beneficial for external vendors (with customers funding 3rd party inefficiencies and product development), but not so much for the customers, leading to highly problematic, slow and extremely expensive projects with poor results.

By contrast, inverting to fundamentally graph-based infrastructures enables massive cost reductions, maximum performance improvements, and radically simplified organizational design — provided it is done correctly.

Of course, realizing these enormous potentials jeopardizes not only external but also internal value positions and corresponding infrastructures. The associated resistance by (perceived or actual) beneficiaries of a status quo or by those disadvantaged by an improvement usually cannot be addressed by technological infrastructure inversion alone:

Technological infrastructures, for their part, are dependent on their organizational context. And the usual resistance to change has never been able to be dealt with effectively by the usual “change management” approaches. Instead, without an empirical leverage point, they tend to have a primarily symbolic effect and to leave the organization suffocating in even more variants of bull excrement.

But empirically effective improvement can also be achieved there by a simple inversion in the treatment of organizational information quality:

In order to draw a qualitative boundary to information, one must know both sides of this boundary (i.e. one must know what one cannot know). By additionally considering the empirical phenomenon of Qualitative Passive Disinformation, resistance to change becomes concretely treatable, which provides an effective rescue from drowning in bull manure.

© 2020-2025 Dr. Thomas R. Glueck, Munich, Germany. All rights reserved.