»Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem.«

Ockham’s razor

Perfect organizations1 are a rare exception, problems are the rule. Not all of them can be solved, often solutions create new problems.

The performance of problem solving can be measured in effectiveness (doing the right things) and efficiency (doing things right):

It is an easily understandable truism that it is better to do the right thing right than to bother with wrong: »right« is certainly more right than »wrong«. However, what is considered right does not necessarily have to be right:2

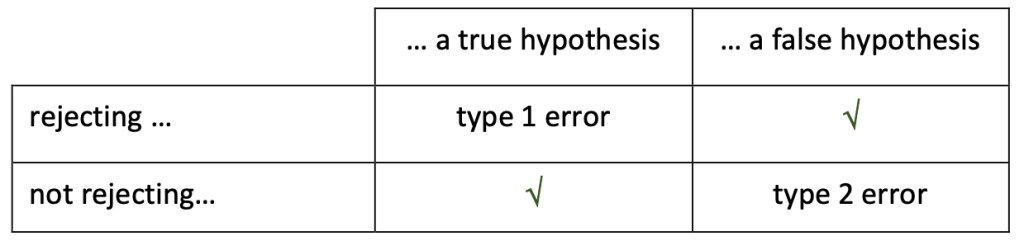

A type 1 error occurs when right is considered wrong; a type 2 error when wrong is considered right.

Such mistakes do not have to be new, but can be very old and come across as very venerable (if not awe-inspiring, even to the point of severe punishment for those who do not submit to them).

According to Locke »this at least is certain, there is not an opinion so absurd, which a man may not receive […]. There is no errour to be named, which has not had its professors: and a man shall never want crooked paths to walk in, if he thinks that he is in the right way, whereever he has the footsteps of others to follow.«

Errors have an almost inexhaustible number of sources, some of them with an astonishing depth of anchorage. They may already be within an organization or be introduced from outside, for example from the socio-cultural environment, publicly funded research, or even be individually driven. Social macrocultures and organizational microcultures regularly influence each other, often true to the old rule: »unius dementia dementes efficit multos« (one fool makes many fools).

The basis for every error saw the light of day for the first time as »innovation«. There are many types of innovation. They can be positioned as follows, with the degree of difficulty of their development increasing from bottom left to top right and their frequency decreasing accordingly:

The development and communication of original,3 empirical innovations is the most demanding, while new bottles for old wine (or completely empty ones) are comparatively easy to obtain and are correspondingly inflationary: The latter is all the more true the more profitable they can be marketed as »solutions«.4

Especially discussions offer many possibilities to create a lot of derivation with little effort, for example by reprocessing another’s territory under slightly modified conditions,5 or by simply criticizing or disproving what has never been claimed and thus trying to force oneself into the new field (or at least get into conversation about it). Schopenhauer’s »eristic dialectics« offers a timeless guideline for such an approach.6

Whitehead implied that almost all truly new ideas contain some degree of stupidity when they are first presented.7 In reality, however, innovation only becomes a source of error and problems when it is misinterpreted, misjudged and misapplied:8 in principle, anything can become an error and cause problems.

Any problem, however, can be someone’s basis for value creation, if not even for existence, which is why truly sustainable solutions can have a destabilising (»disruptive«) or even existence-threatening effect there. The creation of value by means of assessment-arbitrage is a significant basis for social, ecological and economic systems. Depending on the interests involved, even the most serious impairments may therefore be welcome.

Thus consulting9 often does not live best from the final solution of errors and problems, but from their care, deepening and postponement (up to the creation of new problems in need of treatment, provided the recipient does not break this cycle).10 At the same time, not even the person giving the advice must be aware of the fact that he or she is »selling incomprehensible words and ignorance for a heavy price« (Locke) and is at best symbolically improving, but empirically even worsening the situation of the person receiving the advice.11

In the naive and often cited »win-win« case, paradise-like conditions prevail: everyone involved can only profit.12

As desirable as true win-win situations are, they are a very rare exception.13

More realistic and far more frequent are cases in which one of the parties involved is worse off, at least third parties are losing or even both sides lose: Real value creation is no perpetuum mobile (of course, the less you see yourself on the losing side, the more bearable this realization is).14

Consulting provides information, and consulting products can be categorized in many ways. I distinguish the following »product classes«, which can appear in combination in actual consulting situations:15

1) primary: the information itself, regardless of its content or application (e.g. a structure, a »template« or a »framework«)

2) secondary: the information as a model, i.e. in relation to something else.

3) tertiary: a consulting behavior, usually with the aim of influencing or changing system16 behaviors.

For the marketability of consulting services in all product classes, the customer’s appraisal is crucial; whether the service also results in a real improvement for him is actually of minor importance and often difficult, if not impossible, to assess. For the creation of value on the consultant‘s side, it is sufficient if the customer only believes in an improvement (or can at least plausibilise its purchase on behalf of a third party, thus acted »in good faith«): even with senseless17 and harmful consulting products considerable profits are therefore made (often even the largest: the more irrational the buyer is in favour of a product, the less effort is ultimately required on the seller’s side).

On the other hand, even the most sensible and useful consulting products do not have a market value if you do not know them or do not choose them, for example because you misjudge them.18 Finally, the most unlikely are solutions to problems that are not even perceived as such.

Primary consulting products resemble empty shells: They only become more or less useful with their application.

Secondary consulting products can be symbolic or empirical. Poor or non-existent empiricism need not necessarily affect their appreciation: many an advice actually represents nothing more than »higher order symbolism« (i.e. a symbolism of symbolism).19 Even the most empty symbols have at least an »self-empiricism«, and even the purely symbolic can have empirical effects beyond itself if it becomes behaviour guiding. For example, the »Thomas Theorem« states simplistically: »If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences«. Due to their model character, secondary consulting products (with very few exceptions) are inevitably lossy and context-dependent:20 »Every piece of wisdom is the worst folly in the opposite environment« (Ashby).21 The context-dependency of consulting determines its field of application and thus also its limitations. In simple terms, the larger the area of application, the greater the potential for appreciation and, consequently, value creation. A large part of competition on the consulting markets is therefore concerned with the generalising »breaking of patterns« or »paths« of approaches22 which affect an allegedly smaller or less important field of application than the attacker himself is able to cover. This sometimes culminates in the claim to be able to treat »everything« regardless of context, for example by »systemically stepping out« of a problem field, or a postulated »standing above it«.23 In reality, however, the consulting usually becomes all the more empty of content the broader and deeper its alleged area of application becomes: »Oh, there are so many great thoughts that do no more than a bellows: they inflate and make emptier« (Nietzsche).24

Tertiary consulting products can, but do not have to be based on secondary products: In many cases, the consulting service here also consists solely of the »eigen-behaviour« of the consultant. So the consulting behaviour can have empirical external effects, but does not necessarily have to.25 The influence of a tertiary consulting service on an external behaviour can be more or less direct, it can be planned or unplanned. In the planned case, its outcome depends on the quality of the underlying assumptions and their execution, or simply on chance: the more premises (explicit or implicit) there are and the more they differ from the actual circumstances, the less likely it is that the planned outcome will be achieved according to plan.26

Ideally, both the plan itself and its execution are perfect, so that the desired result can be realized just as perfectly. Such ideal cases are limited to completely predictable, trivial systems: system behaviour is all the more complex the less it can be predicted.27

However, complex systems can be »trivialized« by reducing their behavioral alternatives. This trivialisation can be applied to the behaviour itself or to the behaviour-guiding knowledge base: Alternatives that are not known are at best realised randomly.28

Information can expand options of behaviour, but it can also restrict them sustainably (you can become considerably more stupid through learning), which also applies to its transfer in the consulting context; with corresponding trivialisation, even the most serious deficiencies in the premises can be remedied. In the best possible case for the consultant, the system trivialises itself until it finally fits the premises of his consulting service.

In principle, there are the following possibilities for closing the gap between planning and results: either the field of action is adapted to the plan, or the plan to the field of action, or the two approach each other. This equalizing (lat.: identification) can be done in different ways:

In the simpler case, the field of action is identified with the plan only symbolically (and thus simply declares the plan as being successfully realized). This is all the easier the more vague the plan was formulated or the more »analytically challenged« the participants are. In the more demanding case, it is possible to influence the field of action in such a way that the desired result is achieved without any symbolism, i.e. empirically (although there are indeed plans that cannot be empirically realised even with the best will in the world).

Symbolism and trivialisation may help to keep an organization in a more or less stable, dynamic equilibrium and thus to sedate it, but they can also cause considerable disadvantages if the competition is less limited. This can lead to the failure of organizations up to macroeconomic level. For example, Stafford Beer wrote, »our institutions are failing because they are disobeying laws of effective organization which their administrators do not know about, to which indeed their cultural mind is closed […]. Therefore they remain satisfied with a bunch of organizational precepts which are equivalent to the precept in physics that base metal can be transmuted into gold by incantation — and with much the same effect.«29

Now the »laws of effective organization« and the right use of »tools« (or the use of the right tools) are relative, as we have seen. Even the best law can be poorly understood even in the right context, and even the best tool can be poorly applied. And, of course, it is particularly difficult to solve problems which are not even recognized as such in the first place, but on the contrary, where considerable efforts are made to cause, maintain and deepen them.30

In the worst case, from a competitive perspective, one suffers from errors and problems without being aware of them: The Qualitative Blind Spots of Passive Disinformation31 are not easily accessible to autonomous scrutiny. They considerably impair the performance of individuals and organizations, which can lead to massive disadvantages.

Those affected therefore have problems without knowing them, to the point of legitimizing and exacerbating them.

The following picture by M. C. Escher is quite suitable to illustrate this Qualitative Disinformation:

A man is in a picture gallery and takes a closer look at one of the pictures showing a port city. If you let your gaze wander further clockwise from the harbour, you will notice that the man himself is finally a prisoner of the picture. Similarly, in the case of Passive Disinformation, you do indeed possess information,32 but at the same time you are captivated by it (I call this state the »Qualitative Prisoner‘s Dilemma«).

This effect can be simulated with the following experiment. If you close your left eye, fixate the star with your right eye and slowly change the distance to the image, you can observe the disappearance of the circle at the correct distance:

Every person has a blind spot at the point where the optic nerve enters the eye. Although it is actually present all the time, this local blindness is usually not noticed at all: you do not see that you do not see.33

In contrast to the often quoted unspecific, non-qualitative interpretations (which simply refer to non-existent information), the Qualitative Blind Spots of Passive Disinformation actually provide information, although this empirical phenomenon34 considerably hinders the further acquisition of information and its processing.35

So information or knowledge is therefore not only good and useful. Francis Bacon created a central fallacy with his famous dictum that »knowledge is power« (»scientia et potentia humana in idem coincidunt«): In fact, it can (even independently of its content) be harmful and make people powerless much more often than you might think; the quality of knowledge itself is often massively deficient.

The study of errors and fallacies is as old as mankind. Not only the ancient Romans knew that to err is human (»errare humanum est«). To understand and categorize various errors has always been a popular pastime and it regularly provides new skins for old wine.

Apart from the fact that one is always smarter afterwards, however, such studies do not guarantee by any means that the considered cases of error will be avoided in the future, and in fact they repeatedly occur in ever new forms: The fundamental causes of wrong decisions can hardly be treated effectively by symptom symbolism.

In particular, the fundamental problem of knowledge quality is not solved in this way, let alone even touched. The sustainable solution of our basic problem is indeed one of the most difficult tasks imaginable if approached in the wrong way: When dealing with knowledge quality, the main barrier is that the instruments used for this purpose inevitably consist of knowledge themselves – so knowledge is described by knowledge. The progress of knowledge about knowledge itself has thus always been kept within very narrow limits: In addition to the proliferation of categories, there are more or less hidden circular definitions (so-called »circuli vitiosi« or vicious circles up to paradoxes), which for example Plato had already discussed in Theaitet. So the image inevitably remains a prisoner of the image:

This vicious circle can only be broken by a fundamental change of perspective. The basic question can be approached from two sides: in order to draw a line of demarcation for knowledge, you would actually have to know both sides of this line — you would therefore have to know what you cannot know.

My solution therefore looks primarily at this side of the border from a strikingly simple, empirical perspective: in the center of my Knowledge Quality Analysis are disinformation aspects while focussing on the most crucial weakness of thinking: the phenomenon of Passive (or Qualitative) Disinformation.

This knowledge quality concept opens up a consulting niche that is as substantial as it is interdisciplinary and context-independent, with the greatest possible range of applications: the originally innovative, empirical starting point offers new consulting solutions from organizational analysis to organizational design.36

Organizations are (knowledge)ecological systems that exhibit more or less stable, dynamic equilibrium states even in their problem constellations and can be characterized in particular by these.37 It can be assumed that everything that exists is supported (and as long as it is supported, it will continue to exist within this context), which also applies to organizational barriers – regardless of whether they are emergent or are created deliberately.

As we have seen, constraints regularly also represent sources of value creation. This is not least the reason for their sustained support, even if this does not always happen directly or consciously. Where a truly effective improvement presupposes the breaking of organizational barriers, openly or covertly effective constellations of interests can also be affected, which support and promote these very disabilities.

As a result, broad areas of organizational problems elude effective treatment without consensual legitimation, however obvious they may be: »change management« ends in symbolisms, tends at best to further inflation, and in the worst case creates new problems instead of having solved the old ones (although the new problems may also help to displace them).38

The phenomenon of Qualitative Disinformation is a primary and widespread cause of (often emergent) organizational problems. It occurs independently of the political, cultural or ideological context, which also guarantees a corresponding independence in its treatment. This phenomenon thus offers not only a legitimate justification, but also a simple starting point for sustainably effective improvement measures:

Knowledge Quality Analysis enables a conflict-reducing breaking of undesirable barriers which have not been accessible to a solution so far.

Empirical phenomena work regardless of whether you know them or believe in them. Passive Disinformation is operationalizable and operable: mental disabilities caused by Qualitative Disinformation do not necessarily have to be, but you do not have to treat them either if you do not want to. But what are the effects of not treating them?

Competition-relevant areas have always thrived on information advantages. However, as has been shown, supposed information advantages can actually be a serious obstacle: poorer information quality leads to competitive disadvantages. The fact that some disabilities may be commonplace in a certain environment and that »the others are even worse« can be of little consolation: By its very nature, globalised competition pays little attention to cultural boundaries. The few large, globally diversified market participants may be less affected by the loss of individual markets as a result of increasing complexity and instability, but even there, substantial values should not be destroyed without good cause.

Quite apart from the economic consequences, qualitative neglect results not least in legal and ethical responsibility. Decision makers are liable for wrong decisions: Those who can have responsibility, have it.

It cannot be averted indefinitely by the cyclical exchange of consulting fads (quite apart from the fact that catching such waves is not only strategically questionable39, but also helps to build up collective imbalances to a critical level).

How long does a consulting fashion cycle usually last, how long do new consulting markets remain new? Many fashions (Bacon spoke of »idols«) are surprisingly persistent. Some things never seem to become obsolete, many innovations are anything but original:

Go, in thy pride, Original, thy way!—

True insight would, in truth, thy spirit grieve!

What wise or stupid thoughts can man conceive,

Unponder’d in the ages pass’d away?

Goethe

Nietzsche emphasized the eternal return of the same,40 and according to Hegel we learn from history that we do not learn from history: Qualitative Disinformation is a »natural«, renewable resource. In this context the Knowledge Quality Analysis offers a sustainable, substantial source of improvement, which can be used in a targeted, minimally invasive manner and with the best possible effect.

Multi pertransibunt et augebitur scientia.

- On the concept of organization see Glück, T. R.: Blind Spots ↩︎

- This is aggravated by the fact that not every hypothesis can be tested, which can significantly prolong their lifetime — especially if they are not (or cannot be) considered as hypotheses in the first place. ↩︎

- Because one »only understands what one has understood« (hermeneutic circle), original innovation does not usually come about by asking people what innovation they need. Henry Ford liked to say that he would probably only have tried to develop better horses and carriages if he had listened to his customers’ wishes alone. Genuine innovation usually requires offering something that potential customers did not know they wanted before they saw it.

On the other hand, this is also the main weakness of original innovation: »what you don’t know doesn’t exist«, so it has to be made known first in a more or less elaborate way. This is all the more laborious the more the new competes with the old. ↩︎ - The more profitable a problem-solving market is, the more intense the competition becomes if the offer cannot be closed off from the competition, e.g. by protective rights. Thus, a devaluation of innovation in the competition of solutions can occur, for example, through generalization (the solution in question becomes a special case of a more comprehensive concept) or through displacement (for example through modified variants or more or less crude plagiarism). ↩︎

- Vischer calls this a »horizontal arabesque« in contrast to the »vertical rochade« (i.e. generalization). In just under 60 pages, he gives an equally apt and entertaining introduction to the art of successfully marketing pompous trivia using academic examples, which can be applied analogously to cultural trends, management fads and other fashion industries (Vischer, D.: Plane Deinen Ruhm). According to Gracian it is »a great wisdom to understand how to sell the air«: such air markets are highly competitive and jealously guarded. ↩︎

- for a complete and compressed reproduction, see Glück, T. R.: Taboo, »The Confusion of Confusions«. As a rule, the more symbolic the market is, the greater the potential for ostensible or gullible misunderstandings. Empirical phenomena, on the other hand, are much less easy to discuss: they can be perceived or ignored, but are difficult to question. That is why the discussion there then shifts to their evaluations: because the tastes are different and often hardly comprehensible, it is – contrary to what the saying goes – quite easy to argue about them). ↩︎

- which is certainly in the eye of the beholder. After an innovation has established itself and thus lost its innovative character, the opposite is more likely to apply: one considers it to be obvious and self-evident, even if it is the most absurd nonsense. ↩︎

- To illustrate this, here is an older joke, which I have made somewhat anonymous for reasons of academic-political correctness. Please replace »x« and »y« respectively with research areas of your choice (»x« should correspond to your preferred discipline): A group of x- and a group of y-scientists travel together by train to a conference. While each y-scientist has his own ticket, the group of x-scientists has only one ticket in total. Suddenly, one of the x-scientists shouts: »The conductor is coming!«, whereupon all his colleagues squeeze into one of the toilets together. The conductor checks the y-scientists, sees that the toilet is occupied and knocks on the door: »Ticket please!«.

One of the x-scientists slides the ticket under the door and the conductor leaves satisfied. On the way back, the y-scientists want to use the same trick and buy only one ticket for the whole group. They are very surprised when they notice that the x-scientists have no ticket at all this time. When one of the x-scientists shouts: »The conductor is coming!« the y-scientists throw themselves into one toilet, while the x-scientists make their way to another one in a more leisurely manner. Before the last of the x-scientists enters the toilet, he knocks on the y-scientists’ door: »Ticket please!« And the moral of the story: you shouldn’t use a method whose weaknesses you don’t understand. ↩︎ - Here consulting is understood in the broadest sense as a supply of information which can be interpreted as such by the inclined reader. It does not necessarily have to be paid for or provided from outside the organization. On the concept of information see Glück, T. R.: Blind Spots ↩︎

- Such vicious circles very often occur in the symbolic area (particularly noticeable, for example, in psycho cults; Kraus mischievously described psychoanalysis as »the disease whose therapy it considers itself to be«). For a general overview of problem and solution categories see Glück, T. R.: Taboo ↩︎

- On the contrary, the sales succeed usually even the better, the more naive the consultant is: it is not difficult to convince for a convinced person ↩︎

- Even if this gain may only consist of the parties’ belief in it. ↩︎

- Especially the attempt to force it regularly leads to the opposite: »The hubris that makes us try to realize heaven on earth tempts us to turn our good earth into a hell – a hell that only humans can realize for their fellow men« (Popper). ↩︎

- Evaluation can also be erroneous, which helps stabilize countless exchange relationships despite objectively disadvantageous consequences. ↩︎

- These categories allow a complete classification of consulting services that are actually offered and used in practice. ↩︎

- These can be persons, organizations etc. in general, as well as non-humanoid systems. ↩︎

- (apart from the intrinsic sense of the products themselves, of course) ↩︎

- Macchiavelli, for example, emphasized that a prince himself must be wise to be able to receive meaningful advice at all. If such restrictions did not exist, there would be much less successful »confidence tricks« and self-reinforcing »bubble economies« (although bubbles can also be reinforced by consciously taking the risk if the actors assume that a »greater fool« will enable them to profitably exit from it. Apart from this, a decoupling of empirical (»fundamental«) aspects and monetary valuations – also due to weaknesses in reporting systems – is inevitable: Inflation and deflation are the rule rather than the exception, because the really true and genuine value of a good or service is very difficult to determine). ↩︎

- The so-called »Tinkerbell effect« can be used here as an illustration: Tinkerbell drank a poison intended for Peter Pan and could only be saved by »the healing power of imagination«. The »argumentum ad populum« works similarly: here one assumes that something is true because many or most people believe it (social systems are not least symbol communities). ↩︎

- cf. Glück, T.R.: Taboo. The quality of a model can be described by differences in complexity (which also determines the application scale of a secondary product). ↩︎

- it does not even have to be the opposite environment, it is usually enough to change or question only individual premises. ↩︎

- Usually these are not actually breaks, but just alternative patterns that are not necessarily better, but only somehow different, and often even worse. Not infrequently, their distinctiveness remains limited to the symbolic level. Although the belief in symbolism can be very successful in moving (especially symbolic) mountains or in creating new ones, which in turn stand in the way of problem solving and require new consulting services: the »symbolic consulting market« is correspondingly branched and bloated. ↩︎

- For example, »meta consulting« compete with »meta meta consulting«, which in turn are challenged by »meta meta meta consulting«, etc. ↩︎

- the emptiest products often bear the designation »holistic«. As an exception to this rule, generic concepts can be mentioned which can actually have an enormous information content (but which must also be applied accordingly in order to realize it), or those which fundamentally deal with information or knowledge itself: after all, as the smallest common denominator of all disciplines, this represent the most inter- or transdisciplinary starting point of all approaches and thus offer the largest consulting niche with the greatest possible potential for expansion. ↩︎

- There again it may well be the case that it is only a matter of »empirical symbolism« or »symbolic empiricism«: in principle, no empirical counter-value, let alone usefulness, is required to obtain a market price (and this is by no means meant ironically, cf. footnote 15; valuation asymmetries and wrong decisions are a factor of production that must be taken seriously, and in some areas even the most important factor). ↩︎

- cf. Nietzsche: »If you think of purpose, you must also think of coincidence and folly«. ↩︎

- A system is all the more predictable, the less behavioral alternatives it has or knows (although even from complete computability a complete computation does not necessarily follow). ↩︎

- Servan made the following statement in 1767: »A feeble-minded despot can force slaves with iron chains; but a true politician binds them much more firmly by the chain of their own ideas[…]. This bond is all the stronger because we do not know its composition and we consider it our own work. Desperation and time gnaw at chains of iron and steel, but they do nothing against the habitual union of ideas; they only bind them more firmly together. On the soft fibres of the brain rests the unshakable foundation of the strongest empires.« (Servan, J. M.: Discours sur l’administration de la justice criminelle, quoted by Foucault, M. in: Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison) ↩︎

- S. Beer: Designing Freedom.

An entertaining account of the cultural fogging of the mind can be found in the work of Bateson:

»Daughter: Daddy, how much do you know?

Father: Me? Hmmm — I have about a pound of knowledge.

T: Don’t be silly. Is it a pound sterling or a pound of weight? I mean, how much do you really know?

V: Alright, my brain weighs about two pounds and I suppose I use about a quarter of it — or use it effectively to a quarter. So let’s say half a pound. […]

T: Daddy, why don’t you use the other three quarters of your brain?

V: Oh, yeah — that — you know, the problem is that I also had teachers at school. And they filled about a quarter of my brain with mist. And then I was reading newspapers and listening to what other people were saying and there was another quarter fogged up.

T: And the other quarter, Daddy?

V: Oh — this is the fog I created myself when I tried to think.« (Bateson, G.: Ecology of the Mind) ↩︎ - Everything that exists is supported by its environment, otherwise something else would have prevailed (even if it »should« behave quite differently; for example, Stafford Beer coined the acronym »POSIWID« (the Purpose Of a System Is What It Does) to indicate the gap between explanation and actual system behavior). This support is often based only on disinformation or symbolism. In the context of management, for example, »symbolic leadership« is supposed to ensure acceptance »by the workers […] in spite of objective contradictions, and in such a way that they attribute rationality to the leaders« (L. v. Rosenstiel: Grundlagen der Führung). Conclusion: ROSIWIHD — the rationality of a system is what it has done. ↩︎

- cf. Glück, T. R.: Taboo; the metaphor of the blind spot is used in almost any number of ways; to distinguish my qualitative from alternative views cf. Glück, T. R.: Blinde Flecken ↩︎

- in comparison to »simple« disinformation, where there is none or only incorrect information ↩︎

- The physiological phenomenon was already known in ancient times. At the time of Mariotte it was a popular party game for the bloodless beheading of subjects (at court one simply held up the thumb as a fixation point). ↩︎

- as opposed to »only-quantitative« interpretations of the metaphor, in which the designation as a blind spot is only a symbolic placeholder for something that does not exist, or as a non-specific attribute for an error or mistake. Please take some time to become fully aware of this serious weakness with far-reaching consequences. You do not need to know it or believe in it to be affected. ↩︎

- This effect I also call »Qualitative Inhibition«. Passive Disinformation »protects« areas of simple disinformation and its consequences and thus represents (quasi as mother of all misconceptions) a central, fundamental barrier of organization. In particular, it leads to impairments of organizational intelligence and thus to severe competitive disadvantages. »Intelligence« can be derived ethymoligically from the Latin inter-legere (»to choose between something«), and Ashby writes accordingly about its improvement in his Introduction to Cybernetics: »›problem solving‹ is largely, perhaps entirely, a matter of appropriate selection. […] it is not impossible that what is commonly referred to as ›intellectual power‹ may be equivalent to ›power of appropriate selection‹. […] If this is so, and as we know that power of selection can be amplified, it seems to follow that intellectual power, like physical power, can be amplified. Let no one say that it cannot be done, for the gene-patterns do it every time they form a brain that grows up to be something better than the gene-pattern could have specified in detail.« ↩︎

- What Ashby said about artificial intelligence (»he who would design a good brain must first know how to make a bad one«), applies accordingly to the improvement of organizational intelligence: He who would design a good organization must first know how to make a bad one. Qualitative Disinformation is the basic problem of effective and good organizational design (see Glück, T. R.: Fractal Analysis). ↩︎

- hardly anything characterizes a system better than its barriers: they restrict its degrees of freedom and thus make it more predictable (»more characteristic«) ↩︎

- On displacement as a problem-solving variant, cf. Glück, T. R.: Taboo ↩︎

- »It has always been a characteristic of good strategies that they have broken invariances« (Schreyögg). The more scarce, i.e. the less widespread some knowledge is, the greater the information advantage in principle. ↩︎

- »And this do I say also to the overthrowers of statues: It is certainly the greatest folly to throw salt into the sea, and statues into the mud. In the mud of your contempt lay the statue: but it is just its law, that out of contempt, its life and living beauty grow again! With diviner features does it now arise, seducing by its suffering; and verily! it will yet thank you for overthrowing it, you subverters!« Nietzsche: Zarathustra ↩︎

© 2020-2025 Dr. Thomas R. Glueck, Munich, Germany. All rights reserved.